This chapter is about a simple but powerful theory, a theory of balance, and its various implications for education. It is not about budget balance, but rather about what happens when people achieve a good balance between their own learning and creating value for others – work-learn balance. One way to achieve education with such a balance is to work with designed action sampling. There are other ways, as will be shown later in this chapter.

For the practically orientated, a theory may not sound very interesting. But few things are as useful as a good theory of what you are doing.[1] With a good theory, we understand more deeply what we are doing practically when we do science and can therefore make wiser decisions and better achieve our goals.

The theory of work-learn balance is not only an attempt to interpret reality, it is also a goal, a kind of vision for education. We who developed designed action sampling did so based on an emerging vision of a school in better balance. A school where everyone has a good balance between their own learning and creating value for others. Mainly teachers and students, but also other professional roles in educational institutions.

The theory of work-learn balance did not appear out of nowhere. It grew out of many years of action research. Its theoretical roots lie in a broad interpretation of entrepreneurship, being ‘entrepreneurial’ in all aspects of life – whatever that word might mean. But we won’t get into that now. The interested reader is welcome to read more about it in other sources.[2]

Balance between own learning and creating value for others

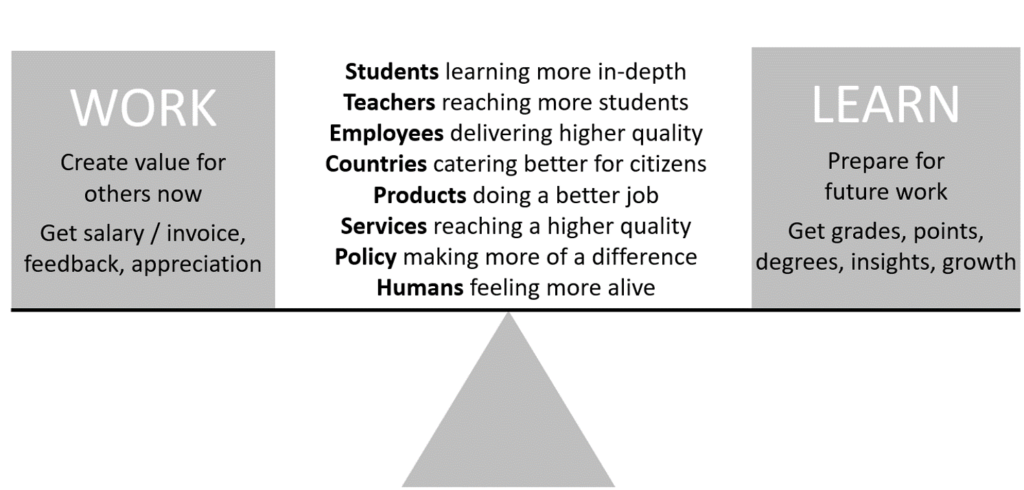

The theory of work-learn balance is based on a special case of the balance between own happiness and meaningfulness with others that was illustrated in Figure 2.2. This is about the moments when we humans experience a good balance in everyday life between our own learning and value creation for others, see Figure 3.1. We chose to call this work-learn balance – a bit of a lesser-known cousin of work-life balance. Indeed, it does not seem to be widely recognised how important this type of balance is for us humans. On the contrary, we usually try to avoid such a balance, by organising human activity into different units that specialise in either our own learning (education/development/innovation units) or in creating value for others (working life/production units). Production units and other routine activities are often streamlined and separated from research, development and education units, which is a pity. The idea is probably that it will be more efficient that way. Learning gained in education is some day in a distant future intended to be transformed into value creation for others. But this is not always easy to appreciate in the moment for those who year after year are isolated in their own learning and rarely get to experience the meaningfulness of doing something valuable for someone else. Paradoxically, in our individualistic society, we humans rather seem to become more motivated by creating value for someone else in ten minutes than for ourselves in ten years.[3]

All people in society could probably do better with more work-learn balance in their daily lives.[4] When people have a good balance between their own learning and creating value for others on a weekly basis, they often feel a greater sense of meaning and purpose in life. This makes them more motivated, committed and diligent. Society then benefits from higher quality, efficiency, deeper learning and better solutions that fulfil their function better for citizens. This is illustrated in Figure 3.1 by some of the effects that can be achieved for students, teachers, employees, countries, products, services, politicians and people.

Figure 3.1 Work-learn balance in everyday life.

The imbalance is most obvious if we zoom out and look at the whole journey of life. Pupils and students spend 15-20 years of their own learning, with no opportunity to create value for others apart from in exceptional cases. These exceptions are carefully separated out into short and isolated one-off experiences per year, such as internships, work experience weeks, degree projects and thematic days. For many students, this imbalance leads to a daily life filled with boredom and a feeling among some students that school is a meaningless pastime[5] , a kind of ‘meaningless school’ from the perspective of some students.[6] Researcher Martin Hugo (2012, p. 31) writes:

One of the fundamental problems in today’s schools is that too many students perceive their encounter with education as meaningless. These students’ intrinsic motivation for schoolwork decreases the more they are in a school where they do not feel involved or do not feel that the content is real.

Then when students enter the labour market and become employees, the imbalance shifts the other way. As employees in the private or public sector, they are expected to devote their full attention to creating value for others. Only exceptionally, and if they have created a lot of value for others, are they allowed to attend one course or lecture per year focussing on their own learning. Even this tends to be an isolated phenomenon that is rarely integrated into their everyday value creation.

The paradox is that in education two imbalances are often represented in the same classroom or lecture hall, day in and day out. Teachers who rarely have time to work on their own learning share space every day with students who rarely get to create anything of value for others. A sad irony.

We believe that such an imbalance is one of the most important challenges facing schools in the next 120 years. Hopefully, this book can become an important piece of the puzzle in the work to achieve an education system with a good work-learn balance. Perhaps our great-grandchildren will be able to laugh a little at those of us who lived in the 21st century when, in 2140, they read the following fictitious quote from Swedish Education Minister Jan Björklund back in 2007:

All the pedagogical ideas that can be invented have been invented, so it is just as well to close down the Agency for School Development.

However, there is an undertone of seriousness in the joke. As Minister for Education, Björklund has successfully pushed Swedish schools towards a relatively unbalanced position in the stultifying pseudo-battle between traditional chalk-and-talk education and progressive fuzzy pedagogy[7] . An education system with a better balance between theoretical knowledge (own learning) and practical application (creating value for others) may seem a more reasonable way forward for the long-term development of education.[8]

Some challenges with teachers’ own learning

Teachers are a professional category with a comparatively strong focus on their own learning. According to union agreements, thirteen working days per year should be used for continuing education in Sweden. However, this time is rarely used systematically or integrated into everyday life. After a professional development day, it is common for teachers to return to the classroom without changing anything. School developer Anders Härdevik (2008, pp. 87-88) writes that this is because change is extremely difficult for the individual teacher and because teachers very rarely receive critical feedback on their teaching in everyday life. The investigator Björn Åstrand (2018, p. 171) writes in a public inquiry about the challenges of teachers’ own learning:

Episodic and fragmented interventions in the form of single lectures or seminars have not, as mentioned above, been shown to have a positive impact on students’ learning […] The main point is that for in-service training to have an impact on teaching and students’ learning, it should take place in the context of the organisation.

Causes of imbalance – specialisation and narrow measurement focus

But how did schools become so unbalanced? One important reason is the industrialisation of society in the 20th century. It was not only factories that increased their efficiency through Taylorism – centralisation, specialisation and efficiency measurements. Taylorism also had a strong foothold in education.[9] One goal of Taylorism is to eliminate the dependence on professionalism and on-the-job learning at the grassroots level, so that anyone can be put to work in production while maintaining efficiency and equal quality. Production line principles and standardising policy documents became the common way of organising both production and education. Value creation for others increased, at least to some extent, but teachers’ own learning and ideas were marginalised. Perhaps the biggest side effect of such an imbalance is a lack of morale and motivation and a sense of powerlessness and meaninglessness.[10] Educational developer Christer Westlund (2020, pp. 12-13) compares educational institutions to an old-fashioned car factory:

All students should produce knowledge and learning in the same subject, at the same time, for the same length of time and in the same way. Should a student be absent, production continues in the same way. Should a teacher be absent, it should be relatively easy to instruct a substitute to temporarily lead the group of students. All students should then need an equally long break and should then be able to switch to another subject, work on it at the same time and for the same length of time as the other students. Then this procedure continues throughout the week. It is then repeated for 38 to 40 weeks over a year and is expected to produce the same results in all educational institutions across the country.

One of the most important Taylorist tools is measurement. Throughout the 20th century, the measurement of education has made great strides. After Taylorism’s time study men with clocks in their hands, neoliberalism and new public management followed, which meant a further strengthening of the focus on measurement. Responsibility for achieving learning goals was delegated down the hierarchy and was accompanied by an increased focus on measurement, control and standardisation.[11] All in line with the market-liberal idea of separating clients from providers so that measurement of outcomes enables comparisons and competition between different producers, thereby driving increased efficiency.[12] Bornemark (2018, pp. 64-65) describes the school’s situation as follows:

Concepts from the industry’s quality control system, such as inspection, quality control, documentation, goal fulfilment/results, market reputation, transparency, customer choice systems, legal certainty and efficiency have become central concepts to capture and define the quality of the school […] The core activities are being displaced by a growing control activity around the core activities.

The reliance on social metrics is based on the illusion that success can always be counted.[13] This illusion has many negative side effects for educational institutions. The focus is on what is easy to measure, such as factual knowledge, literacy and numeracy. These are certainly very important issues, but far from being the sole task of educators. The side effect is that oversimplified measurement crowds out more difficult to measure but equally important effects of education, such as democracy, creativity, commitment, respect for others, initiative, values, etc.[14] Some measurement side effects are what is often called teaching to the test[15] and narrowing of the curriculum.[16] Various tests of students’ knowledge go from being a means to an end, to instead becoming the main goal of the educational institution. As teachers prioritise those learning outcomes that can be easily measured by tests, the curriculum is also increasingly selective and narrow. The more sophisticated and complex dimensions of learning and individual development are de-prioritised. We end up with education that has lost its balance.

Some ways to improve educational balance

In this book, when we move from an unbalanced position to a position of good balance, we call it balancing the education. Just like a car tyre that for some reason has become unbalanced and causes the steering wheel to shake or vibrate unpleasantly while driving needs to be balanced. Fortunately, there are many ways to balance education towards a better work-learn balance. One way is to change the measurement methods used in educational institutions. Researcher Gert Biesta (2009) points to the importance of not only valuing what is easy to measure, but also trying to measure what we value. A more balanced education is therefore not about stopping the measuring. It is both unrealistic and undesirable for humanity to stop trying to measure success.[17] After all, data collection and analysis are at the heart of scientific methodology.

If we want to develop education, we should instead try to develop our measurement methods. This book is written in that spirit. The research methodology described here represents a new and effective way of measuring things that are more difficult to capture in education. It also makes it easier for us to see phenomena and events that were previously too hidden.

Another way to balance education is to compensate with more of what is missing based on the idea of work-learn balance. What needs to be added then differs depending on whether you are a teacher or a student. We will now briefly introduce two different perspectives on balancing – teachers who learn more and students who create value for others.

Both these perspectives are central to achieving better education. Achieving a better balance between learning for oneself and creating value for others is an urgent task, both for those who spend a lot of time in education and for society as a whole. Education with a good balance between learning and value creation fulfils its societal role better.[18] It also makes everyday life more interesting, meaningful and engaging for those who work there. Teachers can develop on a more personal level, and students learn what it means to take responsibility for others.

Balancing for students – value creation pedagogy

The first balancing act concerns students. As their everyday life consists almost exclusively of their own learning, a balancing act for them involves working more on creating value for others. Their learning is perceived as more meaningful when they can apply their knowledge and skills in real life situations and try to create something of value for a real recipient. This could be for someone in the educational institution but outside their own classroom or lecture hall, or, even better, for someone in the community outside the school or campus. This has previously been called pedagogy of work[19] or entrepreneurial pedagogy[20] , but in this book it is called value-creation pedagogy.[21] Although the goal for students is still learning, students’ value creation activities become a means to deepen their learning.

What is meant by this is that the students’ learning is balanced with a little value creation for others, for example that the students can create some enjoyment value, social value, harmony value, influence value or economic value for another person. This is illustrated in Figure 3.2. Learners can then apply their knowledge and skills in practical value creation for and preferably together with others. This leads to increased engagement, higher study motivation and ultimately better study results and grades.[22] This is especially true for students who otherwise feel that education is not really for them.

Figure 3.2 Students’ everyday life is balanced with a dash of value creation pedagogy.

Good examples of value-creation pedagogy can be found at all levels of education.[23] Pre-school children have helped architects design a new building, taught other children how to speak and exhibited their work in the town square. Primary school pupils have read fairy tales in kindergarten, interviewed and told the life stories of vulnerable people, taught environmental awareness to restaurateurs and written opinion pieces in the local press. High school students have made podcasts about fiction, acted as tour guides for newly arrived students, performed children’s theatre and set younger students’ texts to music. University students have trained professionals in biomaterials, organised percussion workshops for children, helped car manufacturers develop electric vehicles and built software for companies.

Vocational education and training usually already has a good balance between learning and value creation, since work-based learning is woven into the programme. Students learn a profession by spending time with colleagues in a workplace, creating value for customers or users. Apprenticeships are perhaps the most balanced form of education. This is because apprentices have about the same amount of time devoted to theoretical knowledge as to its practical application in the workplace. Perhaps this is even a desirable ideal for all education?

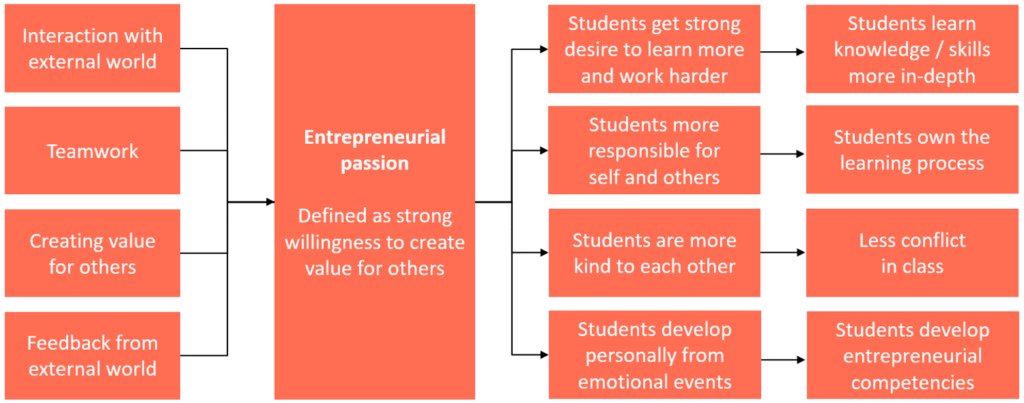

Value creation pedagogy has been shown in research studies to have a wide range of positive effects.[24] When students work with others in the classroom to apply their knowledge and skills to create value for real beneficiaries, and then receive feedback and support from these beneficiaries through personalised interaction, they undergo profound personal development. Such value creation activities lead them to develop a passion for creating value for others. This passion plays a key role in making them study harder, want to learn more, take more responsibility, be kinder to each other and develop on a deep personal level. This, in turn, leads to deeper learning of curricular knowledge and skills, more independent learning and less conflict in the classroom. The effects are summarised in Figure 3.3 below.

Figure 3.3 A model of how value creation pedagogy impacts occur in more detail. The model shows how passion for creating value for others plays a key role in generating strong positive effects on learners. Emotional learning events lead to attitudinal changes, which in turn produce desirable outcomes. The figure is from a published and peer-reviewed scientific article by Lackéus (2020b).

Balancing for teachers – value-creating research

The second balancing act concerns teachers. As their everyday life consists almost exclusively of creating value for students, balancing means that they work more on their own learning. The creation of value for students is perceived as more meaningful when teachers try to learn new things that they can try and hopefully benefit from in their work with students. Such learning has many names, such as in-service training, competence development, collegial learning, action research, action learning or professional development. In this book, it is referred to as value-creating research, since teachers’ learning is, at best, a scientifically structured learning process with the aim of creating value for students. Thus, even though teachers’ goal in school is still to create value for students, teachers learning in scientific ways becomes a means of developing their value-creating ability. Teachers’ everyday life thus also becomes more balanced and meaningful from a work-learn perspective. This is illustrated in Figure 3.4.

Figure 3.4 Teachers’ everyday life is balanced with a bit of value-creating research through a structured learning process empowered by designed action sampling.

With thirteen full days dedicated to in-service training each year, teachers’ imbalance is not as severe as students’. Recently, teacher learning has also come under increasing scrutiny, both in Sweden and internationally. Through decades of research, internationally leading scholars such as Helen Timperley, Michael Fullan, Peter Senge, Donald Schön and Anthony Bryk have demonstrated positive effects on organisational goal achievement, and thus put professional collegial learning on the agenda among teachers.

In Sweden, the major breakthrough came in 2011 when the Swedish National Agency for Education recommended that the government should base the largest ever investment in teachers’ professional development on the idea of professional collegial learning.[25] Three billion Swedish crowns was invested[26] in Matematics “lift” and Reading “lift”, both based on the professional collegial learning model. Although there is no shortage of criticism, the initiatives are regarded as successful, not least because of the focus on professional collegial learning.[27]

Despite this focus and well-funded initiatives, professional collegial learning is still a vaguely defined concept. Something that is missing in the Swedish National Agency for Education’s activities, and also in their definition, is, for example, a strong focus on student effects.[28] In order to also include student effects, professional collegial learning is therefore defined here on the basis of three different elements[29] , see Figure 3.5. Teachers working together to learn new things is a necessary but not sufficient requirement to achieve effects on student learning outcomes. There must also be a change in classroom or lecture hall practices. This change must also take place in ways that lead to improved student outcomes.

Figure 3.5 Definition of professional collegial learning in relation to the three phases of the cyclical work process and various associated challenges.

Emphasising the importance of value-creating research in this book is an attempt to clarify how important it is that we achieve effects on student learning, not just on teacher learning. Scientific dialogue between teachers should revolve around practical activities in the classroom or lecture hall that have the potential to create value for students. Otherwise, there is a risk that we will only have pleasant smalltalk between teachers, a kind of didactic “reassurance club”[30] or “duck pond”.[31] Researcher Veronica Sülau (2019) has studied what happened when the Swedish Mathematics “lift” initiative met a local school practice. She uses the anonymised teacher Bengt to illustrate how Swedish National Agency for Education’s overly narrow definition of professional collegial learning can lead to the phenomenon being reduced and becoming ineffective (p. 181):

Collegial learning is, from Bengt’s perspective, more important than the content, and is about talking to each other among mathematics teachers. About what is less important, so to speak. However, in none of the collegial discussions that form the basis for this study, or in the written reflections, do the teachers talk about how collegial learning should function as a means for them to develop as mathematics teachers. Nor is this something that is explicitly stated by the supervisors in the collegial dialogue. Collegial learning is thus reduced to a mere goal, with an emphasis on collegiality rather than learning. Simply put, when teachers sit together and talk about maths or general education issues, the goal is achieved.

It thus seems important not to let own learning and creation of value for others drift too far apart. We should all endeavour to maintain this balance in our daily lives, whether we are teachers or students. Or, for that matter, entrepreneurs, or employees in any other sector of society. Nor is it enough to have a pious hope that our own learning now will lead to the creation of more value for others later. It needs to be organised for this to happen.

The theory of work-learn balance – a coin with two sides

The two balances now discussed can be said to be two sides of the same coin. The coin itself we call the work-learn balance theory – that any given social environment can have a higher perceived sense of meaning, higher quality and a more clearly stated purpose, if people are encouraged to strive for a good balance between:

- structured, collective and reflective learning processes around new phenomena.

- emotionally powerful experiences where you try to create value for others.

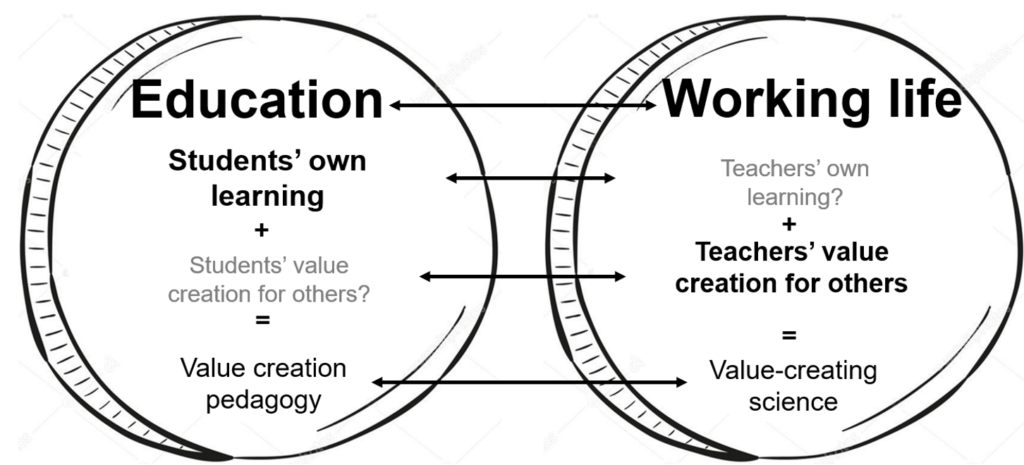

Such balance promotes interest, motivation, commitment, quality and thus performance, effectiveness and achievement. The application of the work-learn balance theory in schools is illustrated in Figure 3.6.

Figure 3.6 The theory of work-learn balance as it can be applied in education for students and teachers. Students’ learning without creating value for others, and teachers’ creating value for others without their own learning, basically illustrate two different sides of the same coin. The coin is about work-learn balance for all people.

In education, the work-learn balance theory can be seen as an interdisciplinary bridge between students’ education and teachers’ working life. By studying two such different phenomena together, we can probably gain a deeper insight and understanding of both than if we had studied them in isolation. Although this book is primarily about balancing the lives of teachers, the ideas in the book are equally applicable to students. Students can also work in a more scientific and structured way when they combine their own learning with creating value for others. Value-creating science can thus be applied to students’ learning as well.

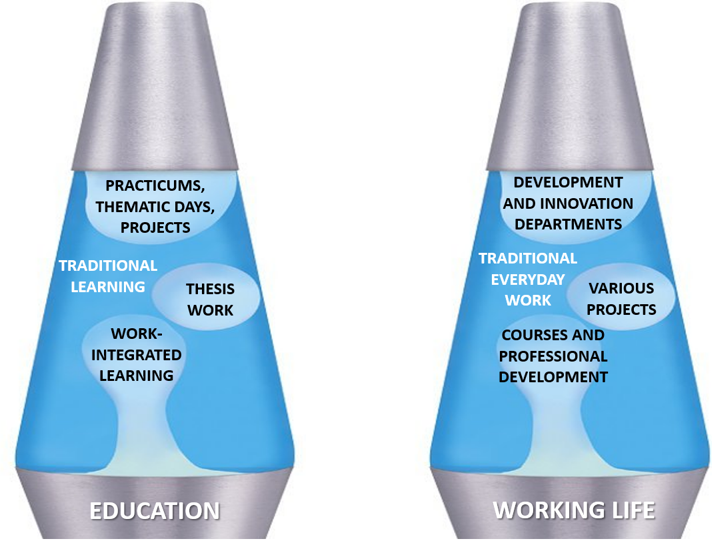

Learning and value creation are like oil and water

Unfortunately, in today’s specialised society, the balance between one’s own learning and the creation of value for others does not arise automatically. On the contrary, they are like oil and water – they separate spontaneously if nothing is done actively, see Figure 3.7. Balance must therefore be created and constantly maintained through conscious leadership and organisation. This is true both in education and in working life. If successful, teachers and students will feel a greater sense of meaning and purpose in their daily lives. They will be energised, achieve more in their work and go further in the search for new knowledge and new ways of working. Ultimately, this brings joy to themselves and to others. The people in education will be better off, and society will have a better education.

Figure 3.7 Value creation for others and own learning are like oil and water. In education, we have isolated oil bubbles of students creating value for others, surrounded by a sea of traditional learning. In working life, we have isolated oil bubbles of employee learning, surrounded by a sea of traditional everyday work.

One challenge in achieving a balanced education is how finely we blend learning and value creation. It is not enough that both perspectives are represented for a year but isolated in time from each other. Since they cross-fertilise each other, we achieve the strongest effects if we get them to mix in everyday life, every day, or at least every one or two weeks. A bit like a good Bearnaise sauce, or a vinaigrette, which contains both oil and water in a fine-grained mixture.

The idea of fine-grained blending of learning and value creation has major organisational implications for educational institutions. Therefore, leadership and organisation around work-learn balance issues are important. Is it really appropriate to talk about separated professional development days for teachers and thematic days or separated practicums for students, if the strongest effects require a fine-grained mix of learning and value creation on a weekly basis? Shouldn’t teacher professional development instead be integrated with everyday teaching? Shouldn’t students’ value creation also be integrated with their everyday learning? Yes, there are many arguments in favour of this. What is difficult is how to do it in practice. We come to that now.

[1] This is a well-known statement that originally comes from Lewin (1951). Read more in articles by Pawson (2003) and Lundberg (2004). What Lewin originally wanted to convey was that many researchers jump too quickly into new measurement tools and run towards some kind of result, without having a deep theoretical understanding of what they are doing.

[2] See for example Lackéus, Lundqvist, Williams Middleton and Inden (2020) as well as Lackéus, Lundqvist and Williams Middleton (2019).

[3] In our research, we have called this the altruistic paradox, see Lackéus (2015, s. 29).

[4] For perspectives on such a balance in working life, see Lackéus, Lundqvist, Williams Middleton and Inden (2020). See also the overview of sense of coherence and meaning (KASAM) by sociologist Aaron Antonovsky, in an article by Eriksson and Lindström (2005). See also the so-called progress principle in the workplace by Amabile and Kramer (2011).

[5] The researcher Martin Hugo writes about this, for example (2012).

[6] A somewhat pointed debate article on the subject can be found on DN Debatt, see Lackéus (2019).

[7] See Hultén (2019, s. 211-224) for a review of the tendency of politicians to present pseudo-problems that they can then show vigour in solving. This issue also returns in Chapter 13.

[8] See also Carlgren (2020), Aspelin (2012) and Lackéus (2019).

[9] Read more about this journey in Au (2011).

[10] For a review of workplace alienation, see Sarros et al. (2002). See also on an attempt to combine Taylorism with trust in employee learning (Adler, 1992).

[11] This is aptly described by Robinson (2011)and also by Ball (1998).

[12] For an in-depth description of new public management, see Karlsson (2017).

[13] For two classic reviews of this illusion, see Barrett (1979) and Porter (1996).

[14] Biesta (2007) has written extensively on this phenomenon.

[15] For a discussion in relation to ‘backwash’, when the assessment strategy guides learning rather than the curriculum, see Biggs and Tang. (2011, s. 197).

[16] See e.g. Darling-Hammond and Adamson (2014) and Crocco and Costigan (2007).

[17] Even the contemporary critic of the measurement society, the philosopher Jonna Bornemark (2018, s. 15)confirms the benefits of measurement but highlights the risks when numbers are always prioritised over reflection.

[18] The value of balancing for teachers is undisputed. The value of balancing for students is not as well studied, but a recent impact study shows strong positive effects, see Lackéus et al. (2020b).

[19] See Freinet (1993).

[20] See Lackéus (2015) and Falk-Lundqvist et al. (2011).

[21] See Lackéus (2016) and Wiman (2019).

[22] See impact study by Lackéus (2020b).

[23] A collection of examples can be found on the website www.vcplist.com, see book about value creation pedagogy.

[24] For a summary of six different studies, see Lackéus (2020b).

[25] According to Kirsten (2020) a key publication was an interim report from the Swedish National Agency for Education (2011) which emphasised the importance of collaborative groups of teachers over longer periods of time.

[26] According to the OECD (2017).

[27] Read more about evaluations carried out in Kirsten and Carlbaum (2020).

[28] According to Sjöblom and Jensinger (2020), Sülau (2019) and according to the evaluation of Läslyftet conducted by Andersson et al. (2019). Principal surveys conducted in 2014, which the author received anonymously and in confidence, also show that the pupil effects of the Maths Lift may be weak.

[29] The three parts are taken from Sjöblom and Jensinger (2020, s. 137) and from Katz and Ain Dack (2017, s. 48).

[30] The term ‘reassurance club’ comes from a speech by Alma Harris at the ICSEI conference in Singapore in 2018, cited in Sjöblom and Jensinger (2020, s. 147).

[31] The term ‘duck pond’ was used by a school leader in a project in which the author was involved.