It first seemed like a failure to guide my students’ actions. But unexpectedly me and my students had stumbled upon a new and innovative way to study on-the-job learning. We spotted a new methodology to visualize cause-effect patterns around action learning, and with a previously unattainable level of detail.

I constantly try to involve my students in my research. It’s both fun and powerful. Many good research insights have emerged through collaboration with them, such as the significance of creating value for others, the power of learning from failure and the importance of various emotionally charged learning events. This week it happened again. An insight that I think may be quite significant emerged from a co-creation session with my students. I had involved them as co-researchers for half a day, or actually, for eight months. We collected a massive amount of data together – around 90.000 words of reflections they’d sent to me and self-coded based on the European Commission’s framework for entrepreneurial competencies (Bacigalupo et al., 2016).

Pushing students outside their comfort zone is good for them

Last Friday we spent half a day analysing this data together. I showed them my current research questions around how to make people more entrepreneurial, handed out visualisations of the data, and then they helped me generate answers based on their own insights and based on the data we had collected together. They went back to their own reflections, discussed what they had learned and why, and then reflected again. Some of their reflections baffled me. I now realize that we’ve stumbled upon a novel and useful way to study learning, with implications well beyond entrepreneurship education, and also beyond education in general. What if we can visualise how people learn on-the-job, without having to disturb them almost at all in their busy work schedules? Here is one such visualisation we analyzed together that shows how learning outcomes differ between easy and hard activities. It shows that self-confidence, perseverance, uncertainty management and ability to acquire resources can be learned, especially if students are being pushed outside their comfort zone.

A video that shows how learning outcomes differed between easy and hard challenges. To watch it, press play.

Making entrepreneurial learning visible

Learning is difficult to visualize. Teachers often use exams to “see” what knowledge students learned. But it is a hopelessly flawed method, especially when it comes to more complex learning, such as entrepreneurial competencies. All human learning relies on not only the cognitive head, but also on the psychomotor body and the affective heart. Competent humans not only think, but they also act and feel. To capture this fundamental fact, many learning theorists rely on the three-fold concept of KSA – Knowledge, Skills and Attitudes. Knowledge is quite easy to assess. But how to develop and assess those skills and attitudes needed to create a better future for society? A fundamental job for entrepreneurial people. A decade ago, faced with this assessment problem at our entrepreneurship programme, we started to experiment with assessing those emotional activities that our students learned the most from. We asked ourselves: “‘What emotion-laden activities do our students need to do in order to learn the competencies we want them to learn?” (Lackéus & Williams Middleton, 2018, p.40).

A master thesis that made me blush

To find out good answers, we involved a student at our programme. He went out and asked his classmates what activities they learned the most from at our programme. He then compared it to what their teachers assessed them upon. It was a revealing exercise that made me blush. It turned out that many of the emotionally charged events that they learned the most from were activities that we didn’t even take into consideration in our assessment set-up. Powerful learning came from activities that we had not previously assessed, such as customer meetings, investor presentations, major decisions in the team, and managing other people (Kjernald, 2014, p.21). I often come back to Kjernald’s decade-old master thesis. It has made a lasting impression on me. I’ve been working on fixing these flaws for a decade now.

A decade-long development of a new assessment strategy

Ever since then, we have experimented with various action-reflection tasks that we expect our students to first do and then reflect upon. This developed over the years into an emotional-activity-based assessment strategy that we wrote about in a book chapter (Lackéus & Williams Middleton, 2018). This strategy is described in the figure below (taken from p.39). We label it a dual assessment strategy, because first we give our students a collection of emotion-laden activities that they must do in order to pass the examination, and then they get to prove to us that they did this by reflecting upon it in a micro-reflection format. One reflection for each emotion-laden activity.

Three major versions of action-reflection tasks

The first version was a Word template where the students were asked to document at least five cold-calls and five customer meetings, and reflect upon what they learned from each of them. I used it for a couple of years. The second major version took many more types of emotion-laden activities into account, and was administered through a digital reflection tool, see here:

https://library.loopme.io/packages/view/5d516e75ef70d4052e2fef44

We worked with the second version for five years, me and my colleagues. It had its strengths and weaknesses. Some reflections became really powerful, especially “Reflect upon a critical / emotional event”, “Have a group discussion seminar around sales” and “Illustrate my entrepreneurial self”. Others were reflected upon by many students just to please the teachers. Two years ago, we therefore decided to pivot a bit, and designed a completely new setup. The collection of reflective tasks had become too unfocused and too theoretical. We wanted to return to the core of what can really make people more entrepreneurial – taking action in interpersonal interactions that result in powerful feedback (Lackéus, 2020).

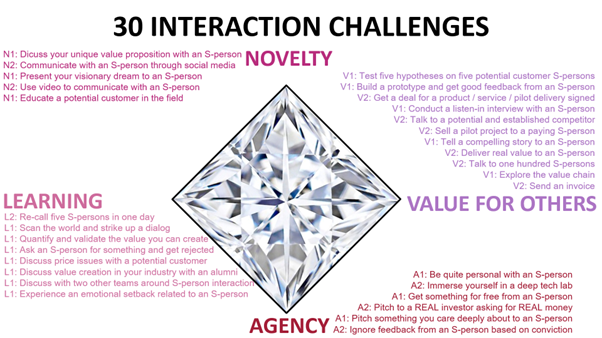

A collection of thirty S-person interaction challenges

The third major version of action-reflection tasks introduced an element of choice. Together with five students who volunteered to help me, I designed a collection of thirty challenges to choose from, of which ten were more difficult. Over a period of six months, each student had to complete and reflect upon at least ten of the thirty challenges – six easy and four difficult ones. Each challenge involved interaction with an “S-person”, defined as a “Significant Stakeholder relevant to your project but NOT part of your project or emotional owner to your project (i.e. NOT your idea partner, other close partner, funder, sponsor, internal coach, corporate coach, teammate, etc)”. I needed to come up with a new term – “S-persons” – that captured more frightening interactions resulting in more powerful learning than talking to people close to you. These thirty challenges can be found in full here:

https://library.loopme.io/packages/view/60c2f799bb857f083e40f2d6

They were organised according to our diamond model of what it means to be entrepreneurial (Lackéus et al., 2020):

Collaborative research on the third major collection of action-reflection tasks

Last week, time had come to sum up two years of this new way of assessing entrepreneurial learning together with my students. My main research question that I invited them to reflect upon was this: What do people learn from being given action-reflection challenges to interact externally? I also asked them to reflect upon the following sub-questions: What is the unique contribution (if any) of these action-reflection challenges, in terms of unique difference this format makes for learning? What is the unique contribution (if any) of the written reflections followed by feedback / discussion? What do students learn from more difficult such challenges? What more action-reflection challenges can we come up with? What is the role of emotions in the development of entrepreneurial competencies? I gave them a pretty substantial deck of slides visualizing their data and helping them get into the mind-set of being co-researchers with me, see all slides here:

Slides summarizing all data collected over eight months

Over the weekend, I read and contemplated their resulting 87 reflections (16,000 words). There was so much insight here! Let me briefly summarize some of it.

Many students applied and appreciated a retrospective reflection strategy

Even though I had presented all 30 challenges to them back in August, now in May many students’ actions had not been impacted by them directly. Instead, faced with a deadline, they searched for suitable challenges that they could reflect upon afterwards. Although not all challenges were suitable to their project, some were suitable enough to provide a retrospective reflection. Two students wrote:

“The thing with these [action-reflection] tasks is that you sort of accidentally have them happen rather than actually pursue them. No one has done more than to retrofit naturally caused events into the [action-reflection] tasks they thought could fit at least fairly well.“

“I didn’t look at the task and thought ‘Oh I should try and do this’, but instead I did the things that I thought needed to be done for the sake of the project and when the time came to reflect, (…) I saw which tasks I had accomplished and filled them out.”

This allowed for an investigation of the unique value of reflection. Many students valued this highly. It helped them stop for a moment, think over and get perspective on their entrepreneurial journey that they would not have had otherwise. It also helped them link practical experiences to literature they had read through our programme. Two students wrote:

“It it easy sometimes to go too fast and forget to reflect upon what you are doing, which can lead to more mistakes and slower personal growth. (…) [The reflective assignment] has made me pause for a second and reflect upon what we have done, why it was important, what the thinking was at the time, and what knowledge I acquired from the interaction.”

“This was a great addition that allowed you to link thoughts with literature you yourself found relevant, as well as inspire to read research that could give clarity to processes that you have done intuitively but did not know there was theory behind.”

Retrofit reflection: A new way to study on-the-job learning

I was surprised to find that so many students didn’t pay attention to the challenges until the deadline approached. At first, this seemed to me like a failure. My intention had been to impact their actions, not only assess them afterwards. But I soon realized that there is an interesting methodological opportunity here. Retrofit reflection represents a novel way to study on-the-job learning. Many practitioners would not accept to be assigned ready-made actions for them to carry out. This could be seen as unsolicited advice, which is highly unpopular among many people. But these same people could probably accept to do a retrofit reflection afterwards, if there were enough challenges to choose from that were relevant to their recent practice. This represents a new way to study informal learning on-the-job. With enough participants, we get cause-effect data on which actions that lead to which outcomes in which situations. I know of no other methodology that produces fine-grained data of this kind. Together with my students, I stumbled upon a methodological innovation. Its potential is of course unknown in this early stage, but it’s still exciting!

Some students were or wanted to be more goal-oriented

There were nevertheless some students who paid careful attention back in August. Their excitement was triggered by some of the challenges, and they put up as a goal to complete some of them at some point. Two students wrote:

“Initially I saw these tasks as goals for the year, and I need to admit, I was quite tempted to reach these ‘goals’. Talking to 100 externals? Hell yes, sounds like a great goal for me to achieve during the year. It felt like it would be fun to conduct these tasks and also learn from external persons.”

“I really liked the talk to 100 people, because we set our sights on that one early and it makes me happy that we achieved that!”

Other students pointed out that with minor adjustments, the 30 challenges could have impacted their actions more profoundly. Two students wrote:

“They could become more useful by being structured more as goals and reflections instead of only reflections. (…) If the challenges instead were to push me more in new directions and set goals for how i acted during the year, i believe that i would have grown more. Now, they did not guide my action, instead they let me understand them more.”

“It also helped to compare with other students. For example, hearing that someone had completed the 100 S-person task early on, motivated me to go out and talk to more people.”

For next year I consider making some changes. I could ask my students to articulate perhaps three difficult challenges that they will try to achieve during the year. Then I might try to incentivize them to achieve this goal, to make it pay off if they reach it. I might also come up with a way for them to exchange ideas on what goals they put up for themselves, and which ones they manage to fulfil, so that they can inspire each other. But all of that said, our programme is already quite action-oriented, demanding and emotional. Maybe we need to be careful not to push our students too hard? Maybe retrofit reflection is good enough here? What do you think? Let me know.

References

Bacigalupo, M., Kampylis, P., Punie, Y., & Van den Brande, G. (2016). EntreComp: The Entrepreneurship Competence Framework.

Kjernald, C. (2014). Activities as a proxy for assessing development of entrepreneurial competencies Chalmers University of Technology]. Gothenburg.

Lackéus, M. (2020). Comparing the impact of three different experiential approaches to entrepreneurship in education. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(5), 937-971.

Lackéus, M., Lundqvist, M., Williams Middleton, K., & Inden, J. (2020). The entrepreneurial employee in the public and private sector – What, Why, How (M. Bacigalupo Ed.).

Lackéus, M., & Williams Middleton, K. (2018). Assessing experiential entrepreneurship education: Key insights from five methods in use at a venture creation program. In D. Hyams-Ssekasi & E. Caldwell (Eds.), Experiential Learning for Entrepreneurship – Theoretical and Practical Perspectives on Enterprise Education. Palgrave Macmillan.

Thanks for posting this Martin. We really must discuss the Design Ed ‘Crit’ approach at some stage, especially the role of divergent thinking and reflection 😉