An intriguing master thesis was completed just before summer by one of our students at Chalmers School of Entrepreneurship, read it here. The student, Christoffer Kjernald, had taken a theory from my research and tested it on his classmates. He labeled it “the proxy theory”, and it basically says that activities can be used as a proxy for assessing development of entrepreneurial competencies. Instead of assessing the entrepreneurial competencies themselves which is very difficult, the assessment could focus on certain kinds of activities leading to the development of entrepreneurial competencies, such as meeting potential customers, presenting for investors, managing other master thesis students and searching for funding. The proxy theory is described in-depth in my dissertation here and in a published article here.

By interviewing 12 fellow classmates approaching the end of their education, Christoffer uncovered a list of 12 different kinds of activity that they stated to be important for their own learning at the entrepreneurship program. The two most important activities were working with the same group of people for a long time and meeting potential customers in an early phase. This is in line with my own research having found that interaction with the outside world and team-work experiences are two of the most important kinds of events leading to development of entrepreneurial competencies, see my dissertation here. He also furthers my research by specifying that different kinds of presentations to others generate different kinds of learning. Presenting in front of classmates generates different kinds of learning than presenting for potential customers. And presenting for potential investors generated a third kind of learning, different from the learning generated when presenting for classmates and customers. This implies that when we label student presentations as a teaching technique, we are describing it way too shallow. The audience and context are very important factors for which learning outcomes are generated among the students.

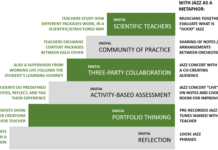

He further found that out of these 12 different kinds of activity, only five of them are explicitly assessed at our master program today. While we today are assessing if the students make cold calls, make school presentations and meet their idea providers, we do not assess whether they make customer presentations, search for funding, manage other master thesis students or take major decisions. As Christoffer points out it is perhaps not so easy assessing activities that are not experienced by all teams. It could also lower the motivation and engagement if students are not doing these activities on their own initiative, but as part of a formal assessment. Still, it is highly interesting to see that activitiy based assessment holds much further potential here at Chalmers School of Entrepreneurship. What does this imply for education programs where activity based assessment is not at all used today? Perhaps this is a straightforward and smooth way of increasing the level of entrepreneurial competencies being developed among students in many different kinds of education and age.