I’ve been a teacher in corporate entrepreneurship for five years now, and a researcher on how to make people entrepreneurial for ten years. Despite this, it’s not until recently that I’ve started thinking deeply about who the “entrepreneurial employee” is. And, perhaps more importantly, how she “is” and “becomes” entrepreneurial in practice. Research has shown that entrepreneurial firms perform better than non-entrepreneurial firms. Both in financial and in non-financial terms, see a relatively recent literature review here.

But research has so far been largely mute on how to make a firm’s employees more entrepreneurial. Some even see it as an oxymoron – an entrepreneurial person is by definition not employed by someone else, the narrow-minded reasoning goes. As if being entrepreneurial were a legal-administrative issue of who employs who. Others think it’s more interesting and effective to search for already entrepreneurial people outside the firm to collaborate with. Static and fixed mindsets abound here.

Entrepreneurial competencies in corporations

My quest for a deeper understanding of the entrepreneurial employee started when I boarded a flight from Leeds to Amsterdam in September last year. On the plane was Dr Margherita Bacigalupo who works for the European Commission’s research centre in Sevilla. We had both been speakers at the IEEC conference, the leading annual meet-up for enterprise educators in the UK. As always, our talk on the plane centred around EntreComp, EU:s increasingly diffused and celebrated framework for entrepreneurial competencies that Margherita is one of the main co-authors of. She told me that they had started investigating how EntreComp can be applied not only to education but also to work-life. It turned into a captivating discussion.

When we said good-bye and went to our different flight connections at Schiphol, I had become fully convinced that the entrepreneurial employee is an important topic to investigate further. After all, most people who could become more entreprenurial in their life are employees, not students. If we don’t manage to make people more entrepreneurial while they are students, we should not give up on emancipating them from a life of creating the same types of value over and over again. A routine value creation based worklife is most often largely void of exploratory value creation. Left alone, most of these people would merely be sustaining the current world of work, not contributing much to creating a better world. This is especially lamentable when we consider that ability and willingness to create a better world is not a trait people are born with, it’s a habit and identity that can be acquired. An entrepreneurial identity. Read all about it in this recent book by my colleague Karen Williams Middleton and others.

Not much focus on entrepreneurial employees

There and then, my research direction changed somewhat. I’ve now been investigating the topic of entrepreneurial employees extensively for about seven months. I’ve ordered about a meter of books. I’ve downloaded countless articles. While I’ve not read all of it, I’ve sifted through a vast amount of literature, relating it to our own research on making people more entrepreneurial in education. To my surprise, not much has been written about the entrepreneurial employee. Most literature on what is often called “corporate entrepreneurship” is focused on the entrepreneurial firm, its organizational and cultural characteristics, and especially its top managers. An entrepreneurial firm is defined as innovative, proactive and risk-taking, sometimes also allowing for autonomy and competitive aggressiveness. There are well-established survey instruments available for measuring a firm’s entrepreneurial “orientation”. Questions used are for example:

Q: How much do you agree with the following statements? (grade 1-7)

- Our firm emphasizes both exploration and experimentation for opportunities

- Our firm seeks out new ways to do things

- We always try to take the initiative in every situation

- The top managers of our firm favor a strong emphasis on R&D, technological leadership, and innovations

The answers to such surveys are provided by corporate executives, especially CEOs. Research is thus focused primarily on the views of top managers, not on the grassroots employees and their more or less entrepreneurial everyday endeavors. Applying this upper echelon approach, scholars have made some impressively rigorous studies. In one study by leading scholars Johan Wiklund and Dean Shepherd, they made thousands of phone calls to business managers. First they asked how entrepreneurial their firm was, and then, one year later, they asked how well the firm was performing financially. It turned out that those firms who were more entrepreneurial were also one year later performing better in terms of profitability and growth. Great news! It indeed seems to pay off for firms to be entrepreneurial. Or, if you wish, those firms who perform well financially can also afford to be more entrepreneurial. Macro-level statistical research cannot really tell the diffence.

Truly rigorous research – but is it relevant?

Still, after about six months of digging into the field of corporate entrepreneurship literature, I ended up with the same depressive impression I have of my home domain entrepreneurship education. Most work is done on a macro level, superficially studying large collectives of people and their attitudes, not so much their behaviors, emotions and related underpinning meanings on a micro level. Survey research is the primary data collection method, and the results are rigorous in mathematical terms. But what do they really tell us about the entrepreneurial employee? Not much, from what I can discern. If anything, being entrepreneurial is treated as a static variable. Either a firm is entrepreneurial or it’s not. Most recommendations on how to become more entrepreneurial are focused on top managers’ attitudes, organizational structures and external stakeholders. If training programs are discussed, the most important factor is to identify and better prepare those employees who are already entrepreneurial. A learning-oriented perspective is largely absent (for a refreshing exception, see this paper). Static, oh so static.

Is the entrepreneurial employee born or made?

The current state of corporate entrepreneurship reminds me of the discussion in the early years of entrepreneurship education research, three or four decades ago. See for example this article from 1985. Back then, a debate emerged on whether entrepreneurs are born or made, and consequently whether it was even worth the effort to train people to become more entrepreneurial. Now we know that while some entrepreneurs are indeed born, entrepreneurs can also be powerfully made and re-made through education and training.

This knowledge seems not to have reached the corporate entrepreneurship domain. Being entrepreneurial is rarely regarded to be a competence that an employee can develop. The question of whether entrepreneurial people are born or made is largely not even asked yet. Instead, firms are advised to look primarily outside their own organization to find entrepreneurial people they can work with. Recommendations are that firms should work with open innovation, since most entrepreneurial people are out there somewhere. Firms should find, attract and work with start-ups, who are deemed to be so much more entrepreneurial than the firm’s own employees. And firms should establish a corporate venturing unit that identifies and then spins out those few entrepreneurial people inside the own firm to newly established small corporate-owned start-ups, thus making them even leave the firm. Oh, irony.

Defining the entrepreneurial employee

Enough moaning about the perceived (imagined?) shortcomings of extant work. What do we at Chalmers aim to do about it? Well, we are currently working on an article for practitioners tentatively titled “The entrepreneurial employee – What, Why and How?”. In this article we will attempt to transfer our twenty years of research and insights in how to make people more entrepreneurial into the corporate sector. If this article is then picked up by practitioners, we might be able to document the outcome systematically to see whether and how it works.

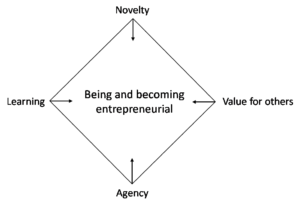

Some of the content of this article will come from our clinical lab based research environment at Chalmers. Through a lab approach of doing research on our own students while in treatment, and also on our alumni post graduation, we have been able to prove empirically that entrepreneurs can indeed be made. Perhaps more importantly, we have also developed a unique and easy-to-use model for how people become entrepreneurial in practice, on a very detailed level. The model consists of four key cornerstones; agency, novelty, value for others and learning, see figure below. We are presenting our first article on this model at a research conference called 3E in May this year.

We believe that this model is transferable to the corporate sector. Entrepreneurial firms will then be defined as firms that encourage a fair share of their employees to take autonomous action (i.e. agency) to try creating innovative kinds (i.e. novelty) of value for their current or future customers (i.e. value for others) through an intensive trial-and-error process of building new knowledge about what works (i.e. learning).

“Value for others” captures the perhaps most salient feature of being entrepreneurial: the never-ending interest in understanding needs, contexts, and how needs can be satisfied in a way appreciated by others. “Agency” can be defined as not only caring but also daring and engaging on a deeply personal level. One can care about a lot of issues but to also act upon them is something different. “Novelty” is about working with new solutions and claiming them – a core part of being entrepreneurial. Last but not least, “learning” is about managing uncertainty and persevere in the ups and downs of an entrepreneurial journey through reflecting upon personal experiences, searching for facts to then imagine new solutions, and sometimes even pivoting into totally new directions.

Future will have to tell whether our assumptions are right. We aim to give this model a try in corporate settings. We have also involved one of the most experienced corporate entrepreneurs we have in west Sweden, an alumni from Chalmers School of Entrepreneurship anno 2000, who as a co-author will contribute with some real-world perspectives from the corporate entrepreneurship domain.

Taking a “from within” perspective to the entrepreneurial employee

The model we’ve developed at Chalmers takes a “from within” perspective, resulting in practical implications for any regular employee at any firm. This model is therefore valid and useful regardless of the current level of entrepreneurial orientation of the employee’s top managers, the firm’s venturing units or its open innovation initiatives. Instead of waiting for the own firm to become more entrepreneurial, or waiting for collaborations with external entrepreneurial people to impact the own department, any employee can now use this model as an inspiration to become more entrepreneurial today. In their own setting and unique situation, and on their own terms. Whether or not they will be supported by their organization and its top managers, is something we here choose to largely disregard. It’s just like in “regular” entrepreneurship, where some entrepreneurs have access to better support structures than others. Lack of support has seldom stopped, and shouldn’t stop, those who are determined to do some serious entrepreneuring.

You can watch a short 2-minute video about our model of being entrepreneurial here:

Being entrepreneurial – a new definition

[…] How is an employee entrepreneurial and why should we care? (Martin Lackéus, researcher, Chalmers School of Entrepreneurship) […]