Since this is a new website, the text has not yet been written for this post. Please come back soon and have a look! We are currently working to produce good and readable texts for all posts about value creation pedagogy.

Let students try a profession

Since this is a new website, the text has not yet been written for this post. Please come back soon and have a look! We are currently working to produce good and readable texts for all posts about value creation pedagogy.

Ask your students questions

The questions we ask ourselves shape our worlds. They shape how we think, act, feel and relate. Questions can transform individuals, organizations, even the world. Questions are key tools in value creation pedagogy, since they shape what students consider, decide upon and ultimately do.

Tweak your teaching

Applying value creation pedagogy is as easy as pouring a drip of color into a glass of water. The addition can be done in a rather easy way, but all the water in the glass changes color. Applied to pedagogy, a teacher can keep most of her teaching plans intact, and just add a small assignment that lets students try to apply some of the knowledge and skills from the curriculum to create value to someone else. Preferably it should be someone they can interact with personally, since human interaction boosts motivation. It can be left to the student to decide upon which part of the curriculum to create value with, which type of value to create and whom to interact with and create value for. A question that can start this process is: “For whom could this knowledge be valuable today?”.

For whom are we doing this?

Students create a large number of artifacts when in schools and colleges. Common artifacts are texts, reports, stories, posters, presentations, videos, plays, concerts and magazines. Such artifacts represent a good starting point in value creation pedagogy. Students and teachers could simply ask themselves before they start to produce a new artifact: “For whom are we doing this?”. This simple question starts a creative process of searching for people who might appreciate the artifact they are about to create. It represents a much more engaging alternative to the common question from students: “Why are we doing this?”.

How can we connect to someone else?

A key aspect of value creation pedagogy is students who get to interact with other people. Tweaking the teaching is then much about how to get some minor aspect of external interaction into the current teaching plans. The external person could be someone else in the class, it could be someone in the school, or someone outside the school. The more unknown and remote the person a student interacts with is, the more powerful value creation pedagogy becomes, but also the more scary it becomes. Tweaking often implies to let students start to create value for and interact with people relatively close to them, such as classmates, other students in school and people outside school they already know.

Mixing learning and value creation

Value creation pedagogy is all about mixing learning activities with value creation activities. Learning is strengthened when value creation activities are added to the learning mix. Value creation is then a powerful means towards the ultimate end of improving learning. The more finely we mix the two, the better we bridge between theory and practice. Learning represents the theory part, and value creation represents the practice part. By asking students to apply their knowledge to create value for others, we also ask them to apply theorerical knowledge in practice.

Learning and value creation are like oil and water

A key challenge in value creation pedagogy is the difficulty in mixing learning and value creation. The two are like oil and water. Unless we stir constantly, they will keep separating from each other spontaneously. It is the teacher who must do the stirring required for the two to mix. This requires energy. Value creation pedagogy therefore needs to be viewed as an investment in time and energy from the teacher. The pay-back comes in the form of more motivated students learning content knowledge deeply, and also in the form of a more enjoyable profession for the teacher. All people involved benefit from a more meaningful educational experience.

Asking bridging questions

One way to stir is to ask bridging questions to students. A key bridging question is: “For whom is this knowledge valuable, today?”. When students get to think about answers to this question, they are forced to bridge theory and practice, at least on a cognitive level. As teachers, we can then take the next natural step in the process. Just ask your students to act upon the answers they come up with. Any potential value they think that they could create through their knowledge can actually be attempted to be created in real-life. This requires them to contact a real person outside their own little group. Scary at first, but transformative when done.

The altruistic paradox

Value creation pedagogy draws much of its power from something that we could call an altruistic paradox. Judging from the examples we have studied, it seems that most people become more motivated by creating value for someone else in 10 minutes, than by creating value for oneself in 10 years. If this is the case, it makes more sense for a teachers to ask their students “For whom could this knowledge be valuable, today?”, than to tell them “You will have use for this knowledge in your future life”.

A motivation deficit in education

Many teachers say that they more or less daily have to answer student questions around “Why are we doing this?”. Answering that they are learning in order to succeed in a test or an exam works quite well for some students. But other students do not succeed in motivating themselves to perform academically based on such answers from their teacher. They want to see meaning with what they do here and now in their life. For these students, value creation pedagogy can provide a new way for teachers to manage and boost student motivation. Connecting the curriculum to some value that is being created here and now for someone else adds a strong sense of meaning to the educational experience for many students.

Altruism is deeply human

Labeling altruism as a paradox does not resonate well with evolutionary biologists. For millions of years, humans have been deeply social, caring and collectively oriented beings. Empathy with others in need is deeply rooted in humans, and some even claim that it is the very trait that makes humans both special and successful. In light of these biological facts, it is perhaps odd to see how little emphasis is given to students creating value for others in most kinds of education today. In the quest for academic rigor and efficiency, some basic elements of humanity were perhaps lost?

A detailed look at the VCP2 definition

The table below shows a detailed definition of value creation pedagogy. It is taken from my PhD thesis from 2016. In this table, value creation pedagogy is defined in a short version and in a long version. The short version only consists of six words; learning-through-creating-value-for-others. The longer version specifies a few different key aspects. Students are supposed to use their competencies when they create value. It is also preferable if the value created is novel in some way.

This is value creation pedagogy

Value creation pedagogy is when teachers let their students learn by applying their competencies (future or existing) to create something of value to at least one external stakeholder outside their own group, class or school. The value that the student creates for someone else can be economic, social or cultural. A teacher needs to be involved for it to be a question of value creation pedagogy, and it needs to happen in formal education. If not, it is rather a question of ordinary work-life experience or at least an extra-curricular experience.

A rare thing in education

Value creation pedagogy is surprisingly uncommon in education. Most students spend most of their days, weeks, months and years in schooling without ever creating anything substantial of value for someone else. Some would even say that letting students create value for others in school or university has nothing to do with education, since the purpose of education is for the students to learn, not to create value for others. They are not there for someone else to benefit from it, at least not there and then, the usual remark goes.

Some exceptions

There are some types of education where value creation pedagogy is more common. The most obvious example is work-based learning and its siblings apprenticeships, internships and service-learning. When students are embedded in the workplace to learn from practice, they inevitably learn through creating value for others. The organizations they learn and work at normally have customers who benefit from the students’ time and effort. The purpose from the educator’s perspective of this set-up is deeper learning, and the means is letting them create value for the organization’s customers.

A pedagogy meriting more emphasis

This website was created with the ambition to put more light on those rare examples of value creation pedagogy out there. These examples tell a convincing story about powerful, even transformative, deep learning of curriculum content. A story about students being engaged on a level they did not previously experience. A story about learning some hard-to-teach competencies deemed crucial in the 21st century of globalization, competition and relentless technological change and innovation.

Developing students’ entrepreneurial skills

Teachers are increasingly expected to equip their students with a set of hard-to-teach soft skills deemed crucial in our increasingly global and competitive society. Skills deemed necessary for students to develop include creativity, initiative-taking, collaboration, innovativeness, self-efficacy, proactiveness and perseverance. Value creation pedagogy is a proven and efficient way to develop these skills in students, often termed “entrepreneurial” skills. This prepares them for life after school by making them more employable and also more successful in their work-life.

Emotional events triggering developed entrepreneurial skills

When teachers let their students try to create value for others, this triggers a variety of emotional events that in turn lead to developed entrepreneurial skills. Some key emotional events triggered by value creation pedagogy include interaction with people outside school, working in teams over extended time periods, overcoming competency gaps, getting honest feedback from people outside class and managing the uncertainty and ambiguity that real-world interaction inevitably leads to. This in turn makes students develop their entreprenurial skills. In brief, when students get to present their work to others who value it and benefit from it, the resulting feelings involve pride, increased self-efficacy and passion leading to strong motivation. If given time and opportunity to repeat this, the students increase their effort, learn more in-depth and enter a positive self-reinforcing cycle of deep learning.

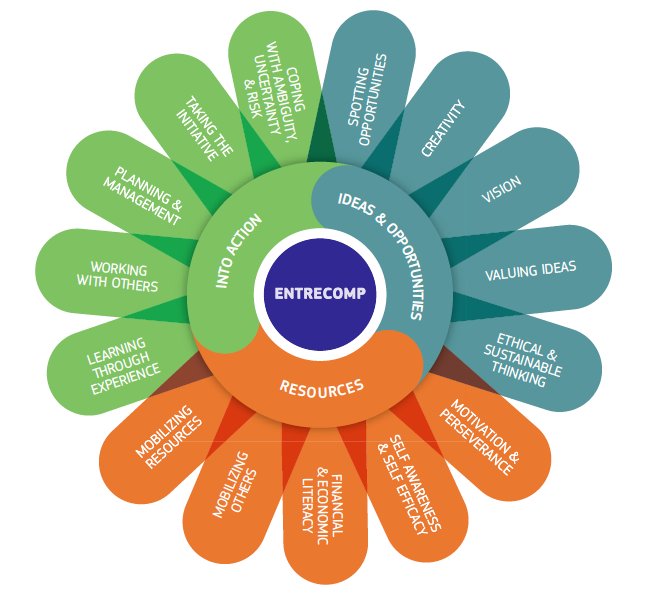

A clarifying framework for entrepreneurial skills

The importance of developing people’s entrepreneurial skills has been emphasized by the European Commission for decades. To support teachers, a framework was recently developed aiming to clarify what skills are deemed “entrepreneurial”. This framework is shown in the figure below. Since it was released by European Commission in 2016, it has contributed to clarifying the intended learning outcomes for teachers around Europe and beyond. When teachers apply value creation pedagogy, they can now use this framework to assess how well they succeed in developing these skills in their students.

Guiding pedagogical variation

A key aspect of good teaching is how to manage the delicate balance between teaching of standardized curriculum content and attending to each individual student’s needs, abilities and learning pathways. Good teachers constantly adjust the curriculum towards their students by adapting and connecting. They nudge and scaffold their students to motivate them to learn the curriculum content. Value creation pedagogy can help teachers in these crucial movements between different pedagogical approaches, answering questions such as: When is it time for traditional teaching? When is it time for more engaging pedagogies that let students apply their knowledge in practice?

The traditional versus progressive pedagogy debate

The balancing act described above is rooted in centuries of fierce educational debate around which of two opposing pedagogical extremes is the “best”. Should teachers focus on traditional lectures, books and exams? Or should they focus on progressive pedagogy, i.e. on coaching their students in creative and engaging problem solving in teams? The bad news is that there is no “right” answer to these questions. The good news is that those teachers who manage to balance the traditional versus progressive pedagogy divide, at least can catch a glimpse of “best”. It is when teachers vary their pedagogy that they have a chance to reach all their students in the “best” possible way.

Bridging the divide through a value creation process

Teachers can use value creation pedagogy to support them in pedagogical variation. When teachers let students learn through creating value for others, they let them engage in a five-step process that balances between traditional and progressive pedagogy. The figure below shows how a value creation process starts in the classroom, letting students generate possible answers to the question “For whom is this knowledge valuable today?”. Then they continue towards traditional education in a search for facts and basic knowledge needed to succeed in creating the value they have envisioned. In the third step, they need to get creative in teams and try to articulate a more explicit value hypothesis. The fourth step includes real-world interactions to try to create the envisioned value. Finally in the fifth step, they return to the classroom and summarize what they have learned. This is facilitated through the reflective question “For whom was this knowledge valuable?”. Here the process starts over again, if time permits.