In more advanced forms of value creation pedagogy, what students do begins to resemble what we in the adult world call professional work. However, children and young people doing professional work can be problematic. In many poor parts of the world, children creating value for others is a dreadful phenomenon known as child labour. Subservient nine-year-olds working in mines, workshops and factories are deprived of their childhood, mental development, health and schooling – we get work without school. Much child labour also takes place in the home, and is defined by UNICEF as when children’s unpaid work in the home exceeds 21 hours per week. [1]

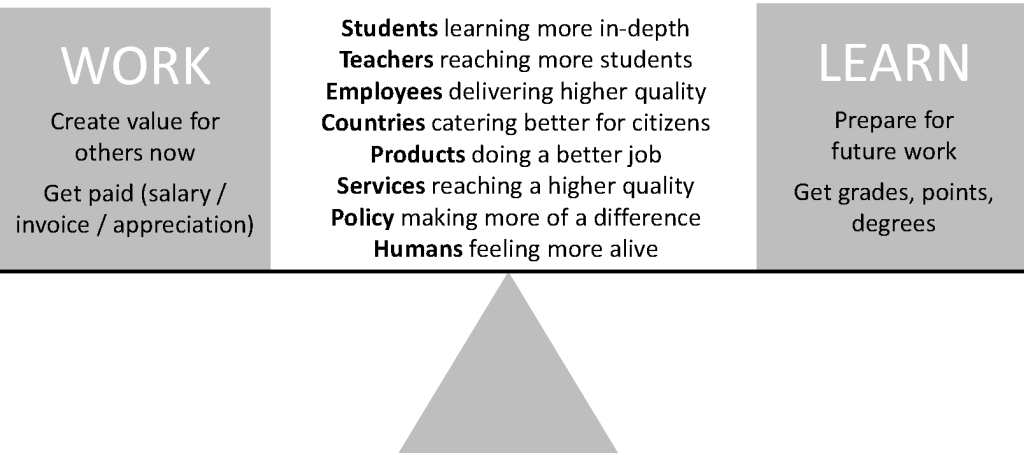

In affluent parts of the world, we see the reverse – school without work. Certainly a much less serious problem. But still a concrete challenge for all those students who do not see the point of theories without practical value there and then, and therefore, for the exact opposite reason, stall in their development. Ironically, then, we need to do more of what in other places is called child labour. In Sweden that may well be okay, because here we are probably as far from child labour as you can get. Personally, I’m lucky if my children help out 21 minutes a week at home. Not all forms of child labour are harmful or even undesirable. What researchers call light child labour can actually benefit children’s development and prepare them for adulthood, as long as the work doesn’t crowd out education or harm the child’s health or psychological development.[2] We need to strive for a balance between learning for oneself and creating value for others, for both adults and students. I like to call it work-learn balance, a kind of cousin to work-life balance. [3]

When people every week have good balance between their own learning and creating value for others, they often feel a greater sense of purpose and meaning in life. They become more motivated, engaged and diligent. This is true for students and teachers alike. Society then gains higher quality, efficiency, deeper learning and better solutions that serve citizens better. This is illustrated in Figure 5.1. In fact, in the same classroom every day, students and teachers often experience imbalance, but in opposite directions. Students are very focused on learning, but often lack value creation for others. Teachers have a lot of focus on value creation for students, but often miss their own learning in their everyday working life.

In this chapter, we will look at some of the different occupations that are often seen when students are engaged in value creation pedagogy. These occupations are good examples of what is known in career guidance as the broad guidance approach, where students’ career learning is seen as the responsibility of the whole school.[4] Within the framework of the school’s regular curriculum and under the guidance of the teacher, students are given the opportunity to try out a profession for themselves in a light and engaging way, linking their work to the world around them and to the knowledge requirements of one or more subjects. Students strengthen their ability to choose a career path that suits them, and at the same time become more involved in school work in the here and now.

In vocational education it is already common practice to have workplace integrated learning, at a regular workplace. Here I rather mean occupations that can be carried out on a classroom basis in ordinary lessons in subjects such as Swedish, English, mathematics, social studies and science.

Some professions seem to be better suited than others as curriculum integrated try-out professions in the classroom. Or maybe we just haven’t yet figured out exactly how other professions can be linked to teaching through value creation pedagogy. After all, we do not yet know everything we would like to know about value creation pedagogy as a phenomenon.

Students as teachers

Let’s start with the profession closest to our heart in school. In my research, I have seen many fine examples of students taking on the role of teacher for a while, in all sorts of subjects. Both for younger students and for classes other than their own. Surely we should not go as far as the classic learning pyramid claims here, that students remember 5% of what they are allowed to listen to but 90% of what they themselves are allowed to teach to others. While many sympathise with the message of the learning pyramid, it has been found to be a classic myth without rigorous empirical support.[5] Instead, let’s note that students who take on the role of teacher are often more motivated to learn more deeply. The challenge is more likely to be what happens at the other end of the pyramid – how students’ teaching appears to the other students who need to sit and listen. Perhaps small groups or short sessions are therefore to be recommended when students act as teachers?

Real depth of knowledge in a narrow field is always a good basis to stand on in the role as a teacher. This is also the basic idea of the university with researchers as teachers. But why wait until then? Canadian researcher Kieran Egan has proposed that students should be assigned a subject on their first day in primary school, which they should be allowed to study in depth every week for twelve years.[6] He calls it learning in depth. Some topics Egan suggests students could spend a decade immersing themselves in are air, light, airports, ants, bridges, castles, caves, clothes, colours, coral, deserts, dust or eyes.[7]

I really like Egan’s idea, being the nerd I am. So do thousands of teachers and students. The idea has been applied in some thirty countries around the world. Students get to feel the joy of really deep knowledge in a field, complementing the superficial curriculum standard idea that students should know a little about a lot.[8] After all, our students need both breadth and depth, so-called T-shaped competence profiles.[9]

Egan’s idea of learning in depth could be a rich source of value creation for students. Imagine a school with five hundred students, each with their own area of expertise that they have spent between one and ten years immersing themselves in. That would be a dream situation for a school’s work on value creation pedagogy. When the students in class 7A learn about corals, the lesson is spiced up with a guest lecture by Sara in 6C who, after six years of study, knows just about everything there is to know about it.

Schools that do not have five hundred experts at their disposal can at least allow students to immerse themselves in complementary ways and then teach each other through short student lectures, preferably across grades and years.

Students as study and career counsellors

Work placements can be combined with value creation pedagogy by allowing students to share their experiences of a profession with other students. Students thus take on the role of career counsellors. In one school, students were asked to carry out a workplace survey which resulted in a report which was then presented at school to other students. A teacher tells us:

Our ninth graders have been given a task during their week of work placement – to report back and tell their peers in year seven what they have been involved in and learned during the week. The students were very engaged and eager to share their stories. In the past, the follow-up of the work placement looked very different, and certainly did not add value to anyone else. The work placement week felt more like a break from everyday life for the students, without either a purpose or a properly articulated goal.

Students’ workplace investigations can also be useful at the workplace and for career counsellors. Students have been tasked with identifying opportunities for improvements in the workplace, helping employers to improve their job interviewing skills and helping employers to improve their sustainability and CSR practices. Students have also helped career counsellors to gain deeper insight into how a particular workplace and profession is perceived by students. Students have also learned about professions by interviewing professionals and sharing insights with their class afterwards.[10]

Students as journalists

Some of the most powerful examples I’ve seen of value creation pedagogy are when students work as journalists. Value is created in two ways – both for those who are interviewed and thus get to influence others with their stories, and for the readers who get to read the students’ articles and portrayals. Students have told the life stories of homeless people, written biographies of elderly people, interviewed ex-criminals, met marine inventors, described young people’s experiences of eating disorders, described elderly people’s experiences of covid-19 and many other interesting things.

First, students seek out and interview different people who have something interesting to say. Then they write texts that tell the person’s story in an interesting way. The texts are then shared on social media, submitted to local newspapers, posted on walls in public spaces, disseminated through their own newspapers and books that are printed and distributed, or published through digital platforms such as Mobile Stories, specifically designed for student journalism. There is also an established prize for students called the Young Journalist Award.

Just as journalism today involves a lot of sound, images and video, students can also photograph, film, record sound and edit. They then also learn to deal with copyright, source protection, press ethics and privacy issues.

Students as social workers and assistants

In my doctoral thesis I wrote about something I called educational economics.[11] The idea was that students spend time and energy creating value for others and gain learning, motivation and a deep sense of meaning in return. While adults need to be paid in return for the time they spend helping others, or else they can’t make a living, students instead have guardians who pay for their living expenses. They can therefore enjoy the luxury of doing good without getting paid, especially for recipients who cannot pay. This is a fifth type of work in addition to paid work, relief work, domestic work and voluntary work. Given that the education system takes up to twenty years to complete, we are talking about a sizeable workforce. Educational economics opens up opportunities to help vulnerable groups that are not fully reached by distributive policies, charity and non-profit forces.

There are many lists of groups considered vulnerable in society.[12] Children, prostitutes, LGBT people, women (young, elderly, foreign-born and victims of violence), people with disabilities and the oppressed. There are a large number of organisations working to help the vulnerable that can be contacted in students’ attempts to work in a value-creating way.

However, it is important that students who help out for free do not feel exploited. In our research on apprenticeships we encountered several secondary school students on work placements who told us that they do much the same work as the workplace’s employees, but without being paid at all.[13] According to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child every person under the age of 18 has the right to be protected from economic exploitation.

There are some tricks to reduce the risk of students feeling exploited. The help they give can be one-off or at least for relatively short periods. After all, it is the first few times we do something that we learn the most. The help can be innovative in some way, so it’s not about doing exactly what is already being done by paid adults. The help can be given relationally, so that students get to meet and build a personal relationship with those they are helping. A clear link to the curriculum and learning objectives and a focus on students learning new things is also important. Then, of course, students can also be paid for the work they do, especially in secondary schools where some apprentices are actually paid under employment-like conditions. Such pay enhances learning as they become more motivated, feel more like part of the team and take more responsibility in the workplace.[14]

In our research we have seen students helping homeless, orphans, prisoners, newly arrived refugees, ex-criminals, politicians living under threat, schools in vulnerable areas, and transsexuals. Charity fundraising is also common and can work. But then there is a risk of losing the relational aspects. Students often don’t get to meet those who benefit from their fundraising efforts. Perhaps the most important source of increased student engagement is then lost – feedback from externals to students face-to-face. At the same time, there may be ways to bring about interaction and feedback even in fundraising work, for example through analogue or digital conversations with charities or with recipients of aid. It is best if students can provide the help on the spot, but this can often be difficult to achieve practically.

Students as biologists and ecologists

Value creation can also be directed at something other than people. Also animals and nature can provide feedback. Plants can become greener, seas and rivers can become cleaner, animals can come back. There are around ten thousand endangered animals and plants, including turtles, elephants, gorillas, pandas, tigers, porpoises, killer whales, rhinos, crustaceans, mosses, lichens, fungi and insects. You can also help nearby forests, bays, lakes, seas and rivers.

In our research, we have seen students helping sharks, squirrels, kestrels and nearby lakes. Many students also get to build birdhouses in Crafts. Others may help tend a farm plot at or near the school. Students’ outdoor educational work is an inexhaustible source of learning, not least because the challenges facing wildlife today are far greater than conservation policy and non-profit forces can handle.

Teachers who want to have students work as biologists can draw inspiration from various non-profit organisations working in nature conservation. In Sweden, for example, there is a nature school association, an outdoor association, a field biologists’ association and a national network for the promotion of outdoor-based learning. Research on outdoor education in a 2012 thesis showed that students remember better and learn more when they sometimes get to experience the outdoor environment as a classroom in mathematics and biology.[15] However, outdoor education is most common in preschool, pre-primary and primary schools. The older the students get, the greater the risk of sedentary desk-based work.[16] Perhaps value creation pedagogy combined with outdoor education can get older students out of the classroom a little more often? Because when the student gets out, and also gets to help, the skills come in. We get powerful whole-body learning.

Students as chefs, dieticians and restaurateurs

In many cultures, offering each other food is a common way to show friendship, appreciation and togetherness – truly an ultra-social act.[17] Food is such an important part of life that the opportunities for value creation for others are great. It is therefore not surprising that many examples of value creation in schools revolve around food. We have seen students writing down recipes and cooking at home, or giving the recipe away to a friend. Students have also baked and sold cookies to raise money for a class trip, written cookbooks with recipes from around the world, text- and video-blogged about food, and even reached out to food influencers. Exhibitions have been organised with a focus on getting people outside school to think more deeply about what the food they eat actually contains.

In a school in Växjö, a collaboration with a local haulage company began, where students put together simple meals and recipe cards for truck drivers, as well as preparing small tasting portions for delivery to the haulage company. The aim was to teach the truck drivers how to prepare nutritious food that could easily be taken into the cab. Having worked in the transport industry for many years myself, I know how difficult it can be to eat well when you’re on the move. Having students come to the rescue about this problem was a fun and unexpected turn of events for me.

At a school in Sundsvall, students raised money for a class trip by hosting a three-course dinner in the home economics room. Each student had to sell three envelopes. At a school in Eskilstuna, students cooked traditional Finnish sausage soup together with Finnish speakers at the Tunagården retirement home. At a secondary school in Lysekil, the public was invited via advertisements in the local press to public lectures on Ireland’s history with appropriate food, evenings that were packed each time.

As long as students are not considered to be engaged in a permanent activity, there are no rules preventing them from occasionally taking on the role of hosts for small or large groups, entirely within the framework of home economics teaching. Imagine what good relations this can create between the school and the surrounding community. Perhaps in combination with adults coming to school to talk about their profession and then being invited for a bite to eat.

Students as nursing assistants in nursing homes

Many schools allow students to visit nursing homes. The forms vary greatly. Often it is a case of young and old coming together to share experiences and gain new perspectives. Students are also often invited to offer the elderly various art and music experiences based on aesthetic school subjects. Students have also been known to cook for the elderly. The job of carer includes many tasks that students on temporary visits are not allowed to try, such as heavy lifting and intimate hygiene, but at least they can contribute with empathy, compassion and just those relational cosy moments that many carers too rarely have time for in a stressful everyday working life.[18]

One of my favourite examples is from Varberg and is called senior surf. Students at many primary schools in the municipality teach elderly how to use tablets. The elderly learn how to surf, play games, take photos and do banking. The students bring with them the joy of teaching and helping the elderly, while strengthening their knowledge of Swedish, social studies and technology.

Students as fire engineers

There are not many examples of students being allowed to work as engineers. A fun exception was when students were asked to do a fire safety report on their own home. One student talks about his view of the task:[19]

It was quite difficult. [I learned] to pay more attention in the home and what things are flammable and what is needed to make it fire safe. [I learned about] organic chemistry.

Students as sanitation workers

Keeping clean and tidy is a timeless value in both urban and rural areas. At a school outside Kungsbacka, the Keep Sweden Clean campaign became a starting point that was adapted to the local community based on the motto Keep Kullavik clean. Students were asked to consider the question: for whom should it be clean?

In three schools in Sundsvall, students campaigned on behalf of the regional housing company Mitthem. The students educated residents on how food waste should be handled so that the public sector avoids unnecessary additional costs. In another primary school in Sundsvall, students were asked to think about how to improve the design of garbage bins. Perhaps an interactive bin will encourage more people to throw their rubbish in the right place? The students’ ideas were then presented to staff at the environmental office, closely followed by journalists from the local radio station. More general examples include young people helping to clean up beaches, forests, streets and schoolyards.

Students as architects and urban planners

As soon as a new building, park, street or facility is to be built where people will live or work, there is room for children and young people to participate and influence the process. It is part of the mission and professional ethos of architects and urban planners to take on board the views and ideas of citizens, including children and young people. Children’s perspectives on urban planning are included in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and is also a cornerstone of democratic planning processes.[20]

I have seen a few examples of value creation pedagogy where students work with architects and urban planners. The clearest example is a collaboration called Architects in Schools.[21] Students were involved in designing a new neighbourhood, a new playground at a pre-school, a new residential area, a new playground and a new park. They had to create mood boards and build scale models. They also had to use visualisation techniques to draw a prototype of a new building. The work took place over several years and was linked to mathematics objectives, social studies, Swedish and technology.

There are many other examples of urban development where children and young people are consulted. In Stockholm’s new master plan, students from fourteen schools participated.[22] However, this is not always done in an pedagogically thought-through way, which represents an untapped potential for strengthening knowledge development and motivation to study.

Students who get to try other professions

This chapter has provided an overview of the occupations that appeared in our various research studies and sample collections. I think this is only a start. Students can probably try out many more professions in the context of regular education and under the guidance of their own teachers. Pick up an occupational directory and look for occupations that might fit with what is happening in your classroom. Some professions where there should be potential are librarian (advising on books), property manager (looking after someone’s house), accountant (doing the maths), investigator (writing in-depth reports), web designer (designing a nice website), software tester (testing if apps work), research assistant (collecting data), health and safety inspector (inspecting workplaces), animal keeper (helping on a farm), leisure leader (organising leisure activities), personal assistant (helping different people) and surveyor (measuring the area of plots of land).

[1] See https://unicef.se/fakta/barnarbete

[2] See Bhukuth (2008, s. 393).

[3] See Lackéus (2021, pp. 47-65).

[4] See more in Lundahl et al. (2020, s. 36–46).

[5] See Letrud and Hernes (2016). The pyramid can be found by googling “learning pyramid”.

[6] See Egan (2010). See also summary of Stivaktaki’s (2017).

[7] For a longer list see http://ierg.ca/LID/how-we-can-help/topics/

[8] Stivaktakis (2017, s. 17) writes of curricula as “a mile wide and an inch deep”.

[9] Read more about people with T skills in Berger (2010).

[10] See Lackéus and Sävetun (2019a, s. 50).

[11] See Lackéus (2016, s. 70).

[12] See for example www.jamstalldhetsmyndigheten.se/

[13] Read more about this in Lackéus and Sävetun (2021).

[14] See Lackéus and Sävetun (2021).

[15] See Fägerstam (2012, 2014).

[16] According to Anders Szczepanski, see article in Skolvärlden (Wahlgren 2012).

[17] See Graeber (2001, s. 44 och 70).

[18] Se Beischer (2012).

[19] See Lackéus and Sävetun (2016, p. 36).

[20] See examples of how it can be done in the thesis by Nilsson Lövehed (2020).

[21] The idea originally came from Ingrid Svetoft at Halmstad University. Read more about architects in schools in Lackéus and Sävetun (2016, s. 47–50).

[22] See City of Stockholm (2017).