In this chapter, I take a more detailed look at what value creation pedagogy is. Word by word, I go through key details and perspectives. It will be a bit of word-twisting, because if our words are limited, the world we live in will also be limited.[1]

I’m not the first to focus on students’ value creation for others in education. Medieval apprentices and Freinet’s pedagogy of work were far ahead. Several of my contemporary research colleagues have also touched upon the idea before.[2] But perhaps value creation pedagogy is the most specific semantics that has been proposed. I often think that the accelerator pedal we today call value creation pedagogy has always been there. With a whole host of pedals for teachers to choose from, however, too few feet have hit the exact pedal this book is about. A more specific semantics puts the headlight on a rarely used accelerator pedal that has been shown to make the educational car rush forward like a newly charged electric car. There are of course many more nice accelerator pedals – other educational ideas that give different desirable effects, but you can read about them in other books.

The meaning-seeking student

Research certainly takes time. After four years of work, we had come up with four words – learning by creating value. I wrote about this in my licentiate thesis in 2013.[3] But what happened then was that many people misunderstood us. They believed that we meant that students would learn by creating value for themselves. Which all teachers already work with every day. So we had to spend two more years researching two more words – for others. I wrote about these two words in my doctoral dissertation, which was completed at the end of 2015, and in a research article published in 2017.[4] Focusing on “the other” creates a deep sense of meaning in us humans. Meaning-seeking is in fact one of humans’ strongest driving forces.[5] A telling example is the so-called parental paradox. Why do so many want to have children when it is so obviously hard and stressful? Well, because it increases the sense of meaning in life.[6] Own happiness and meaningfulness with others are two different phenomena, for both parents and students.[7] Value creation pedagogy can thus be a way to reach unmotivated students tired of school – perhaps it is the lack of meaning they are tired of?

Six words in six years

I do not know how time efficient we were when it took six years to research a new combination of six everyday words. But the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein had probably been pleased. He loved linguistic issues and emphasized the importance of broadening our views with the help of everyday language. In my research, I have been able to clearly see how these six words broaden the views of many teachers.

When I try to trace in retrospect how it was possible to expand with two such short words that change so much, it is difficult to find the exact time in the mailbox. However, my published research articles provide clues. Words that are published can never be changed afterwards, so it’s a bit like searching among frozen thoughts. The first place we wrote about the phrase learning-through-creating-value-for-others was in an article from 2016. I and my supervisors then wrote about how students’ value creation contributes to bridging the classic gap between traditional and progressive education.[8] Traditional education often means teacher-centered lectures for passive students, solitary student work in silence and exams. Progressive education is instead said to be about student-centered, interest-based and active learning, often in groups.[9]

Our 2016 article was also a way to promote a better balance in schools between sharply differing perspectives, rather than further contributing to the trench warfare between traditional “chalk and talk” teaching and progressive “loosey-goosey” pedagogy. In the article, we call value creation pedagogy an educational philosophy. Even today, I do not know if I should call it an educational philosophy, a method, an approach or a way of working. Students’ value creation can express itself in so many different ways. Here in the book, I opted for calling it a way of working.

A longer definition of 31 words

There is also a longer definition of value creation pedagogy:[10]

Let students learn by applying their existing and future competencies in attempts to create something, preferably novel, of value to at least one external stakeholder outside their group, class or school.

However, these words did not take 31 years to arrive at, but they came about already in the summer of 2015 when I gradually started writing my doctoral dissertation. The definition is described in more detail in Table 1.1. The rest of this chapter gives a detailed description and discussion of each phrase.

| Longer definition | Explanation |

| Let students learn | The main purpose is learning, although students often perceive it as the purpose being to create value for others. |

| by applying their existing and future | Students may apply competencies they already possess and those they are now learning for the first time. |

| competencies | The exercise aims to develop both knowledge and skills as well as attitudes. A summary word for all this is competencies. |

| in attempts | It is the attempt that counts. If no value for others is created, learning can still occur. Students learn a lot from failing. |

| to create | This is a creative exercise. Students are expected to create something that did not exist before. |

| something, | the result is some kind of human creation (artifact). A physical (can be touched), intellectual (ideological) or cultural (social) creation. |

| preferably novel, | That it is new is not a requirement but is desirable. From new for the student to new for the world. The more novel creation, the more emotional process. |

| of value | It should be possible evaluate the creation – hopefully the creation then also turns out to be valuable |

| to at least one | At least one external stakeholder needs to be able to give feedback about the value that was created or not for him / her / it (can also be animals / plants). |

| external stakeholder | The more external the recipient of value, the more powerful the exercise becomes, but also the more frightening and complex. |

| outside their group, | A first step is to let students do something valuable for other students in the class. |

| class | The next step is stakeholders outside the class but within their own school, within the safe boundaries of the school. |

| or school. | The most powerful step is to involve stakeholders outside the school. But also the most frightening and complex. |

Table 1.1 Detailed definition of value creation pedagogy.

Let students learn…

Value-creating activities are a means of strengthening the end goal of student learning. It is by letting students create value for others that we better achieve the goal of deepening students’ learning. However, the difference between means and ends can cause confusion.[11] Some teachers ask me what would happen to the school’s core mission if students are allowed to focus on creating value for others. I think the question is reasonable given the steady stream of pedagogical trends and ideas we have seen over the years that often disturb teachers’ focus on the core mission. Do we really get more learning by spending a little less time learning? I understand if this can feel a bit backwards at first glance. Who believes that we get to our destination faster by leaving the motorway and instead taking a smaller road? How many vocabulary tests should now be replaced with eating mold cheese?

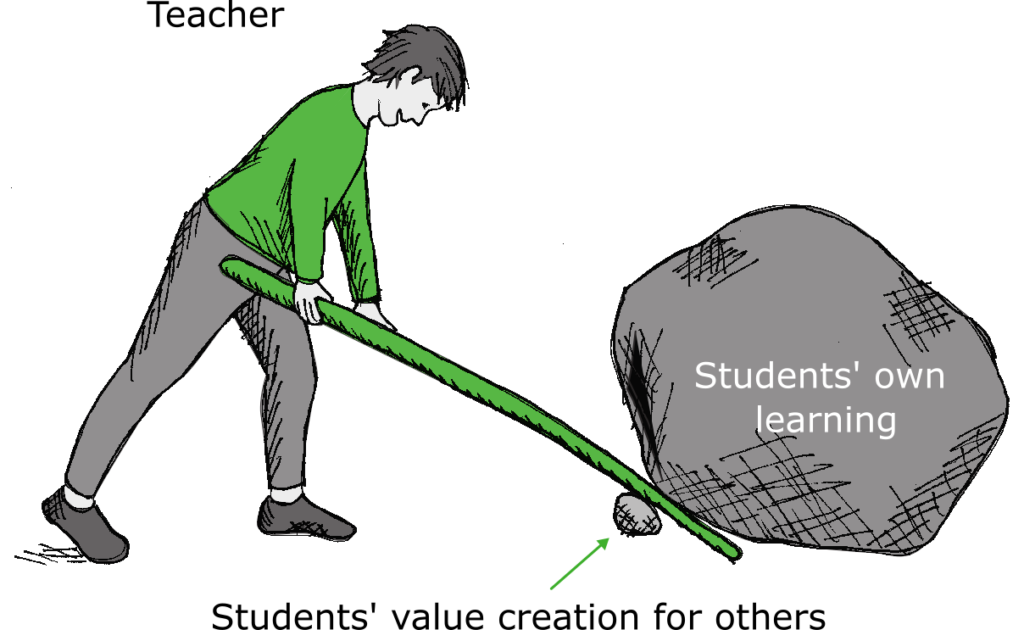

What we have seen is that something that may initially feel like a detour here becomes an exciting shortcut. By devoting say 3-5 percent of the time to strengthening students’ sense of context and meaning, we get much more effect from the 95-97 percent of the time that still focuses on learning. It becomes like a leverage effect, see figure 1.1. The teacher succeeds better with the help of the skewer. A small stone (value-creating activities) helps moveing the many times larger stone (students’ learning). If the students for a while get to feel that the goal is to create value for others, they will be strengthened in their learning of knowledge and skills from the curriculum. Means and ends do not even have to be part of the same process. A value creation process in language class can spill over and have a positive effect on students’ involvement in completely different school subjects. A bit like a butterfly effect of learning.

Figure 1.1 Students’ value creation for others as a lever for strengthened learning.

… by applying their existing and future …

Learning is strengthened when knowledge is used in the real world. That’s how theory and practice are mixed. The focus can definitely be on topics that are currently being treated in a specific subject. At the same time, previously acquired knowledge and skills play an equally important role. In-depth and meaningful learning is often based on newly acquired knowledge being integrated with what the student already knows.[12] Such reinforcement of meaningfulness then helps in retaining knowledge in long-term memory.[13] For me, for example, the Spanish word bocadillo has stuck in my head forever. I can still clearly see in front of me that sandwich stand in Madrid where I tried to apply my theoretical knowledge practically.

The value of linking theory to practice may be obvious for many teachers, but how do we make it happen in practice? Here, value creation pedagogy can help teachers. Students get support in integrating new and old knowledge and skills, simply because everything is mixed naturally in “real” situations. The multifaceted reality seldom respects the strict separation and sequencing of the curriculum in different subjects and learning objectives.

… competencies…

Knowledge, skills, attitudes, feelings, beliefs, values and physical movement patterns are sometimes simplified into a single word – competencies. This word represents a very broad view of what learning can be. For me, the word competencies has therefore come to represent a higher level of learning. A key advantage of value-creating activities is that students’ learning is broadened to include the entire creation we humans constitute. Body as well as soul. We are now touching upon an important point, so let me explain what I mean in more detail.

Early in my research career, I fell head over heels for researcher Peter Jarvis’ theories on human learning.[14] He wrote, like few others, about the crucial role of emotions in learning, that it is the whole body with its network of hundreds of billions of empathetic nerves that learns. Not just the cerebral cortex. For me, who had experienced a kind of learning-by-burning that ended abruptly in a plush sofa, Jarvis’ theories felt right on target.

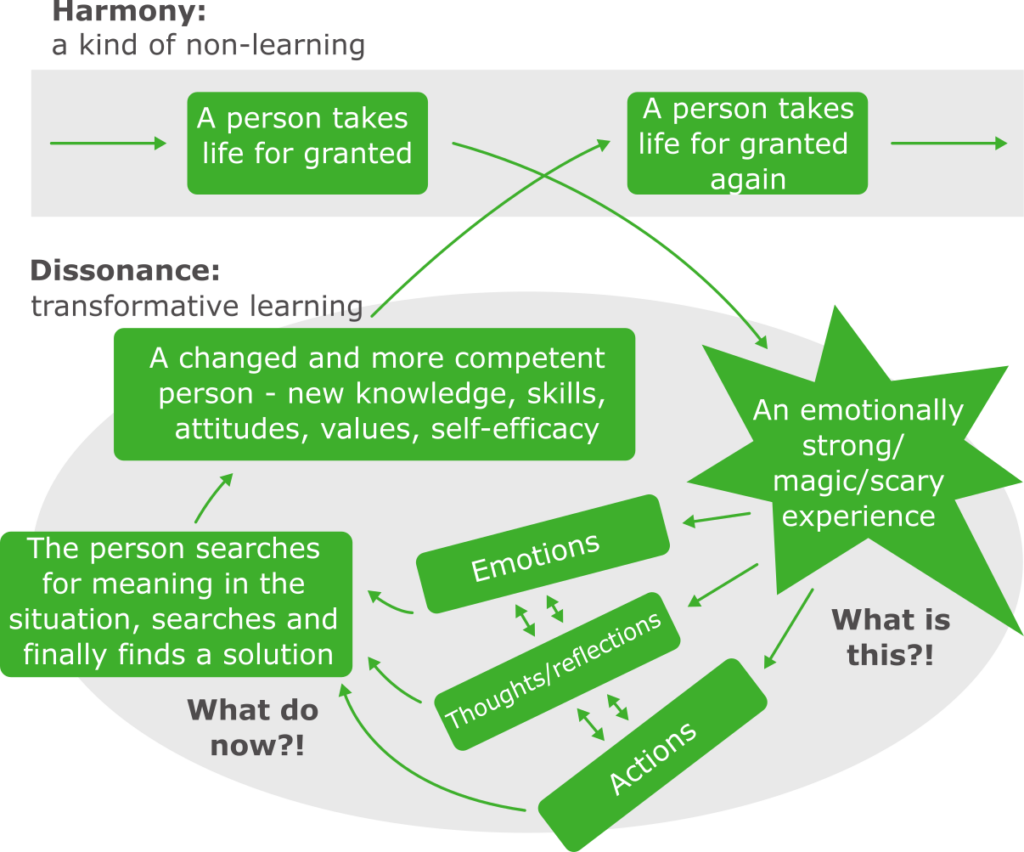

We tend to like when our students are happy and harmonious. But according to Jarvis, harmony is a situation of non-learning. What is needed for us humans to learn in-depth are emotionally strong experiences marked by dissonance, perhaps confusion, perhaps even a bit of magic. This is illustrated by Jarvis with a few different figures on learning, summarized in Figure 1.2 below. If we want to achieve deep learning, we need to leave the calm but boring harmony of the straight line and dare to enter the dissonance bubble where students have to stretch a little bit outside their comfort zone.

But how can teachers make students experience emotionally strong experiences without throwing everyone involved into impossible complexity, assessment splits and painful uncertainty? Here I see value creation pedagogy as a functional and practically feasible way to achieve Jarvis’ vision of such powerful whole-person learning. If we succeed, students develop complex skills, not “just” isolated knowledge, skills or attitudes. Now, the word competencies is a strongly simplified word for what students can be expected to learn from value creation pedagogy, but it is in any case more versatile than talking about “just” knowledge, skills or abilities. I want you to think about all this when you see the word competencies in this book in the future.

Figure 1.2 Dissonance-based learning. Inspired by Jarvis (2006, pp.20-23).

… in attempts …

As is well known, reasonably difficult tasks are preferable.[15] But what is reasonably difficult when it comes to trying to create something valuable for others? At first glance, this may seem very difficult, perhaps even impossible. Many teachers who have asked their students to create value for others have also told about the initial confusion a task of creating value for others can cause among students. Therefore, it is important to clarify that it is the attempt that is important. It can even be said that many students probably learn the most from their failed attempts to create value for others. However, this is not to say that teachers should maximize the level of difficulty, or that it would be good for students to never succeed.

Challenges need to be given in appropriate doses and gradually increased. Then we hit the narrow corridor called “flow” where we balance on the fine line between anxiety and boredom.[16] The challenges we face are then in balance with our own ability. For my own part, I ended up in six months of flow when I went to an English-speaking real estate agent in Madrid. He gave me a room with a talkative and charming gentleman in Argüelles named Juan Carlos who then woke me up every morning for almost six months with a happy “¡Hola Martin! Qué tal?”. My anxiety about becoming homeless decreased, but I never got bored. I learned fluent Spanish in one semester and at the same time got to create some economic (room rent) and social value (good company) together with Carlos.

Some confusion should not deter you as a teacher, even when students are worried, protesting or demanding more clarity. Instead, we can use the confusion as a lever for enhanced learning. Students are forced to stop, think, turn and turn things around and finally move on. Then with revised mental models and deep learning as a result. But the confusion can be of the “right” kind. Researchers often talk about productive and unproductive confusion.[17]

I myself try to strive to be clear about what is to be done (create something of value for someone else), why we do this (because it strengthens our own learning), how it should be done in practice (yes, that’s what this book is about), but not say much about how it will go for the students. It’s up to them. And they need time. Not necessarily lesson time but calendar time. Give them a week to think about it.

However, teachers need to be prepared to support students when they experience different types of negative emotions such as dissonance, headaches between expectations and outcomes, feelings of impossibility, worry or anxiety, fear of failure, misunderstanding, frustration and much more. At the same time, it is precisely these difficult-to-digest emotions that build the basis for the euphoria and arousal a successful attempt to create value for outsiders can result in. Just as in a roller coaster, it is not possible to imagine peaks without the occasional deep valley. When we leave the straight line in school without much emotion bubble and instead sometimes go into the carousel of dissonance, we have to deal with both positive and negative emotions among students, and also among teachers. In fact, this is precisely why the effects on students’ learning become so strong. It’s the emotions that do the trick.

… to create something…

We humans have always loved to create things. The evolutionary history of our species provides many examples of this. Mastering fire, creating practical stone tools, creative use of red ocher paint in various rites and cave paintings, development of linguistic symbols for communication and myth-making, construction of various floating fabrics and not least new methods of using the earth.[18] The author Lasse Berg writes about homo habilis, also called handy man, who already several million years ago had a unique handiness in creating things.

Handiness is one of three timeless and uniquely human strengths our species possesses that can help explain the power of value creation pedagogy. Two other uniquely human strengths are social ability towards others and creativity in relation to different challenges and opportunities. Sure, there are animals that possess handiness, social ability and creativity, but no other species on earth possesses and uses these three abilities to the same extent as humans. This has given us enormous benefits over millions of years, and largely explains why our species has become so dominant on earth. Berg writes that these abilities have made us invincible.[19] What if we could take advantage of them a little more often at school to make students join us? This is exactly what value creation pedagogy can contribute with.

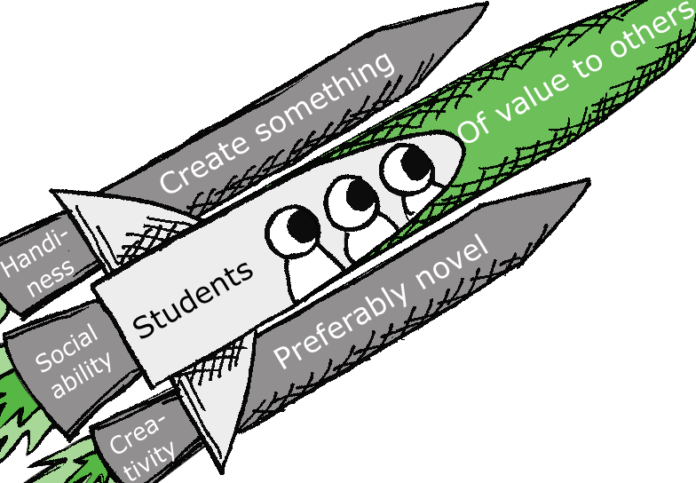

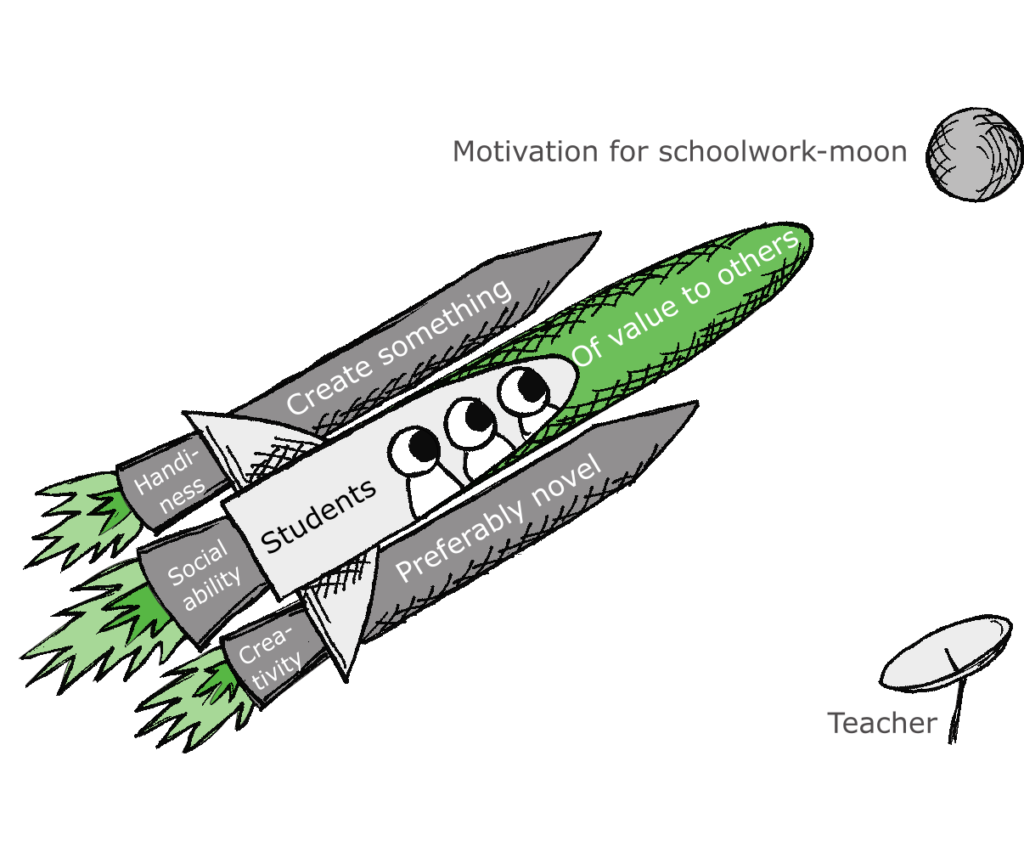

Figure 1.3 below shows the three strengths in relation to value creation pedagogy. The space shuttle in the figure is on its way to high student motivation for school work. It is powered by three launchers filled with three different types of liquid learning oxygen. We can call it handiness oxygen, socializing oxygen and creativity oxygen.

Figure 1.3 Space shuttle on its way to increased student motivation for school work. The shuttle has three launchers filled with three different types of liquid learning oxygen. The figure shows the students in the driver’s seat, a place we adults should give them when we can. Teachers can instead coordinate the space shuttle’s journey across the sky of learning from a control center on the ground.

Letting students create things gives our space shuttle power from one of the three launchers. Students usually enjoy creating things, just as most people do.[20] It can be drawings, reports, posters or brochures. It can be digital creations such as websites, blog posts, videos, podcasts or games. It can be social creations such as campaigns, sketches, sporting events, performances and games. Allowing students to work with concrete creations can deepen learning in an extremely powerful way, and is a central piece of the puzzle in many different socio-cultural learning theories in the spirit of Vygotsky.[21] Through their own creations, students understand the knowledge material better.

Isolated creation, however, is seldom enough all the way forward. If the purpose of the creations is vague, or if no one cares about the students’ creations, well then the space shuttle still risks crashing into flume and indifference. Therefore, the large launcher with socializing oxygen in the middle is needed, which we will get to very soon. But before we get to the space shuttle’s main launcher, we’ll take a closer look at the bottom launcher that is filled with creativity oxygen.

… preferably novel…

Creating something new that becomes useful to others is often called working creatively.[22] Now that the school according to the curriculum is to stimulate students’ creativity, it is fortunate that there are aesthetic subjects. There, students get to create new things in, for example, music, carving, drawing and sewing. Some of the students’ creations also benefit others, which is required for it to be called creativity in the full sense of the word. I have met many craft teachers, art teachers and music teachers who say that value creation pedagogy comes naturally to them. This is how they have always worked with their students, they say. Great.

But the school still needs to do more. Creativity is one of the most important and most in-demand skills in our society.[23] Routine occupations are increasingly disappearing and are being replaced by occupations that require the ability to think anew, deal with new situations, identify new problems and create new solutions that help others. Creativity is also an important source of meaning in the lives of many people.[24] All teachers therefore need to participate in the work of stimulating students’ creativity, not just the aesthetics teachers. Many aesthetics teachers can also do more to make students’ creations more valuable to others.

Creativity in school is admittedly difficult.[25] Many of the school’s cornerstones hamper students’ creativity, such as clear routines, focus on predictability, detailed curricula for what is to be taught, focus on not making mistakes, assessment in relation to what is right, focus on results, individual work, competition, grades and much more.[26] Some even say that knowledge and creativity are in fundamental conflict with each other.[27]

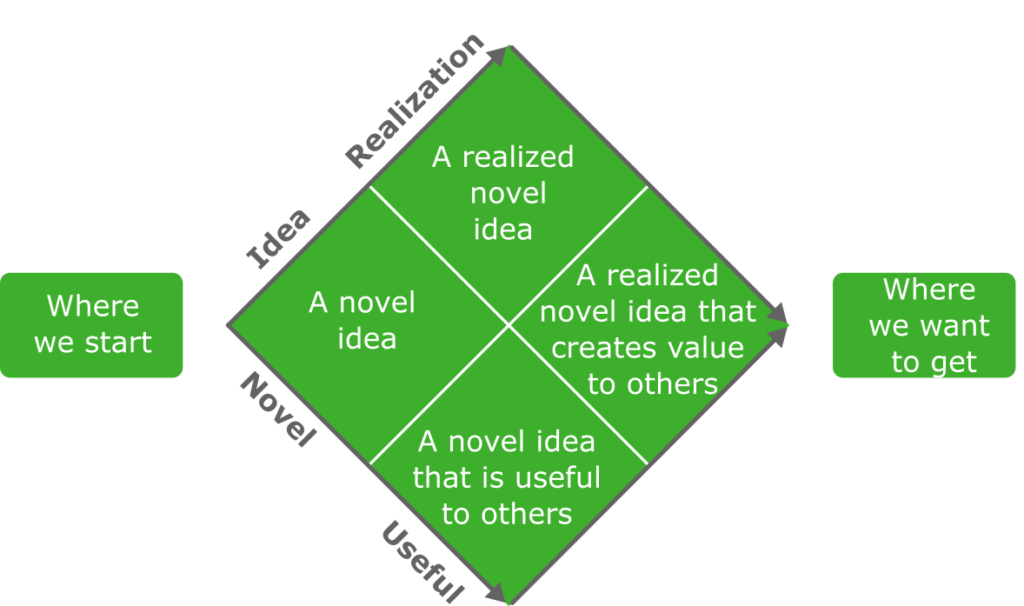

To make creativity manageable in school, it is therefore often simplified into a focus on coming up with new ideas.[28] It is of course beautiful with intuition and imagination as a basis for thinking anew.[29] But it takes more than that to develop genuine creative ability. Students need to be able to put their ideas into action in practice, preferably in authentic social environments. Students also need to try to get the new creation to be of use and joy to someone else, preferably people outside the school. There are thus four perspectives to keep track of, see figure 1.4 below. Here, value creation pedagogy can facilitate teachers’ work with creativity in practice. When students are allowed to work to create value, they naturally get to experience all four central perspectives on creativity. Students who are allowed to take action and try to create new value for others then develop their creative ability. The value that is created can be new to themselves (everyday creativity), new to the whole world (genius creativity), or something in between.[30] But what exactly is value? We’ll get to that now.

Figure 1.4 Guide to what is required to promote students’ creativity.

… of value …

What does the word value really mean? I was asked that question one day in early November 2015 when the world-famous professor Saras Sarasvathy was at Chalmers in Gothenburg to oppose my dissertation one last time before it was to be printed. Life as a doctoral student is seldom glamorous, but sometimes it shines. It was a magical moment when she examined the idea of value creation pedagogy. She really liked the subject and said that if John Dewey was alive today, he would probably have been a professor of entrepreneurial pedagogy. But she also saw something no other reviewer had seen before. I had completely forgotten to write about different meanings of the word value in my dissertation on value creation pedagogy. Embarrassing!

The ensuing Christmas did not turn out quite as usual. Instead, I found myself buried in all literature of the world about this partially ungoogleable word in five letters. I learned that value as a concept has been studied for hundreds of years by economists, mathematicians, philosophers, anthropologists, sociologists, psychologists and many others. The word got its own chapter in my dissertation, and I have continued to read and write a lot about value ever since. For the interested reader, there are many in-depth texts.[31] However, such in-depth study can fill an entire book, an entire life even. Therefore, this will be a very short summary of the word’s intended meaning.

The word value can be said to have one, two, three, five, ten, seventeen or more meanings, depending on the context and who you are asking. When the word is given one meaning, it is often economic value that is meant. “What is the product worth?” the buyer wonders and then thinks of the price in monetary terms. Many economists like to see the market price of a phenomenon as its true value, and then mathematically calculate supply and demand. Sociologists instead divide value into two meanings by distinguishing between value and values. They let economists handle value in the singular and study many different types of values in the plural. Within sustainable development, three meanings are often discussed – economic, social and ecological value. With a three-phronged income statement in their annual accounts, organizations can show how the year turned out from three different value perspectives – so-called triple bottom line accounting.

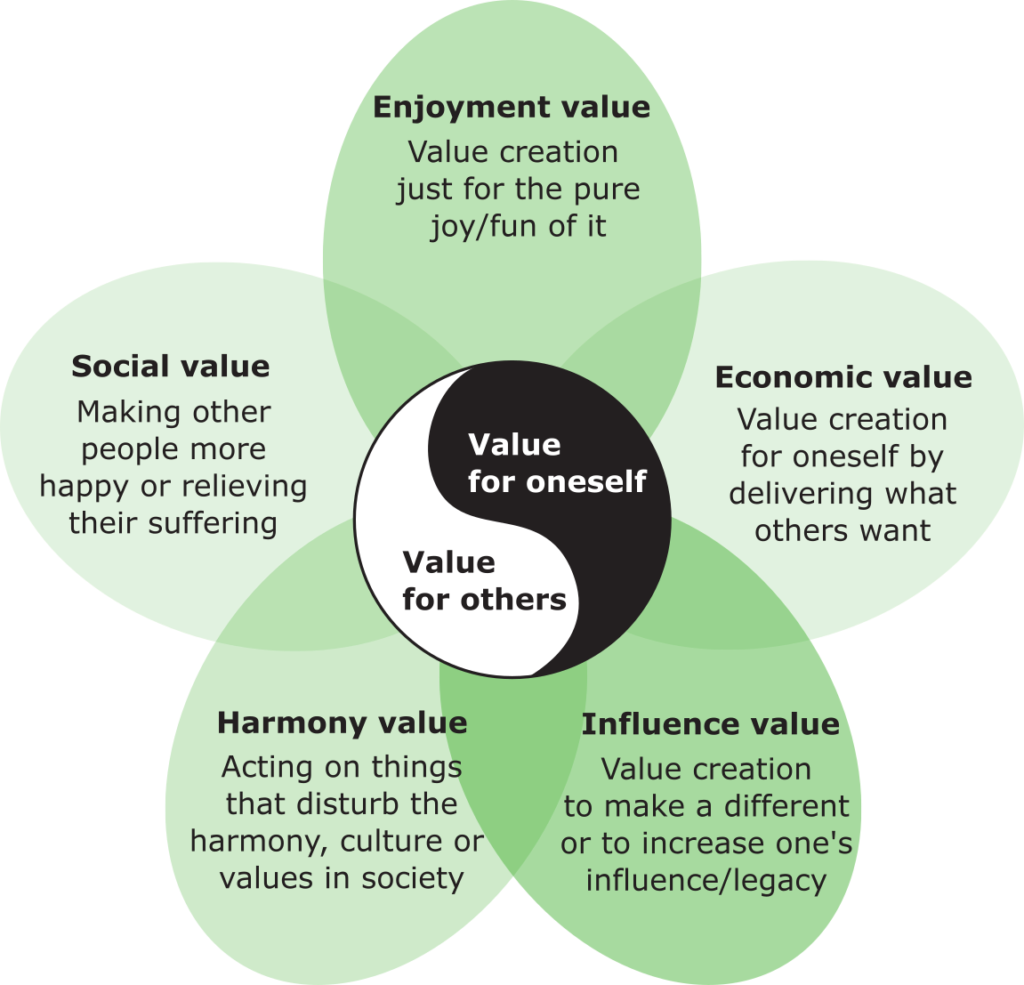

In the book I will use a division of value into five meanings which I briefly go through below and which I first wrote about in my dissertation. I also distinguish between value for oneself versus value for others, because the five values can be created either for oneself or for others. It gives us a total of ten meanings, where the classic perspective economic value for oneself accounts to a mere tenth. This gives us a value flower as shown in Figure 1.5. The flower is a simplification. It is probably possible to come up with hundreds of different kinds of values. We must also not forget value beyond what we humans like. We live in an anthropocentric age where, out of recklessness, we often put humans at the center, to the detriment of animals and nature.

Now follows a brief review of the five times two perspectives in the value flower.[32]

Economic value is often function-oriented and transaction-based, calculated in the money paid or saved when various goods and services are exchanged. Economic value for oneself is usually called a salary or payment and is something you get when you have created or delivered something of value to others. Economic value can also be about economizing, trying to be more resource efficient. Some also help others create financial value, such as banks that help their customers manage money.

Figure 1.5 The value flower with its ten different perspectives on value (5 × 2). Translated from Lackéus (2018).

Social value is about making people happier or alleviating their suffering. It is a broad category – what people value in life is multifaceted and partly subjective.[33] Some examples of social value are having close relationships with other people, expressing their identity, learning new knowledge and skills, improving their personal health and feeling safe and secure.

Enjoyment value is when you do things out of pure joy and to have fun. It can be deeply engaging and creative work tasks, cultural experiences or experiences where you get to do or learn something new. Such activities are often both challenging and inherently inspiring and can lead to a mental state of flow where people are completely mesmerized, feel competent and sometimes lose track of time.[34]

Influence value is when people gain influence, reputation, power or other influence on others in society, for example for managers, politicians or celebrities. Influence value can also be about everyday actions that deeply affect another person, such as parents who raise their children, employees who help customers and colleagues at work or teachers who help their students grow. Central to influential value is people’s desire to perform, a deeply human driving force.[35] People’s need for meaning in life can also be satisfied by gaining influence over others.[36]

Harmony value is about the value of a harmonious whole, either culturally or in relation to justice, ecology, equality or the public good. It is an often collective and conditional type of value that is situation-dependent and based on common values.[37] It is therefore often a more complex type of value that comes into focus in more advanced societies. An everyday example is that many cinema visitors want popcorn, even if they otherwise never eat popcorn.[38] A more complex example is the UN’s seventeen goals for sustainable development,[39] a kind of value model with seventeen meanings. They are about trying to reduce global poverty, hunger and climate change and instead promote health, equality, ecology, security, sustainability, inclusion and more.

Value for oneself is often called self-interest or egoism. Sensory experiences, satisfaction, power, wealth and becoming a winner are often discussed here. This perspective is many economists’ favorite perspective and is illustrated by their view of human as a homo economicus – an economically self-optimizing being who needs to be given incentives to do good for others so that it also benefits oneself. The goal is value for oneself and the means is value for others.

Value for others is often called altruism or being a social being. Here, creative actions that make a difference and that give a sense of togetherness and meaning together are often discussed. The focus is on relationships, job satisfaction and commitment. Many sociologists see human as a homo sociologicus, a social being who does good to others by her own inherent power. The goal is social cohesion and the means is that value is created by many and for many. A beautiful collectivism, but it is probably seldom that simple. In practice, value for oneself and value for others are often closely linked,[40] which is illustrated by yin and yang in the value flower. Doing well by doing good.

These ten different perspectives show the incredible breadth of different kinds of values that students can create for others when they work to create value in school. But why is that other person so important? We’ll get to that now.

… to at least one external stakeholder …

We humans actually care much more about others than we think.[41] Unlike all other species on earth, we have a strong mutual altruism, we really care about each other.[42] Evidence of this unique behavior can be found in biology as well as sociology, anthropology, psychology and evolution. It’s about dopamine, but also about empathy, morality, pathos of justice, peer pressure, equal treatment and respect. Contrary to what many people try to make us believe in today’s individualistic society, we humans are usually really polite and helpful to others, and we also like to be.[43] Cooperation is in fact such a hallmark of our species that evolutionary scientists call us humans “ultrasocial” beings.[44] The author Lasse Berg (2006, p. 265) describes our social side as follows:

We have a desperate need to belong together, of human closeness, of being able to help each other in larger groups, of getting appreciation, of getting to feel the warmth of solidarity. It is this community that gives our lives its meaning. We perish from loneliness.

There seems to be a deep human need to help others. Not only our loved ones, but also complete strangers. We humans seem to prefer to stick together, cooperate and uphold moral principles.

Now perhaps avid egoists object to this sugarcoated version of human nature by saying that all these forms of kindness and helpfulness are just a kind of disguised or delayed egoism. A way to appear in better days, to be part of the gang, to get own advantage later, to avoid exclusion or to get a higher status in the group.[45] Purely evolutionarily, there are also clear survival gains from collaboration.[46] This is especially true of species that manage an equal-for-equal strategy – helping those who contribute and punishing those who exploit others.[47]

Here, perhaps, it does not matter much exactly why we humans love to help outsiders. In this book we do not have to solve the almost eternal question of whether humans are capable of pure altruistic selflessness or not. What matters is that so-called prosocial motivation theory works well in practice to motivate and engage school students. Social interaction with external stakeholders in order to try to help them seems to be a surprisingly powerful learning oxygen, and deserves its place as the largest and most important of the launchers on our spaceflight towards motivation for the schoolwork moon.

Surprise has been a recurring pattern during the decade I have spent studying students who try to create value for others. Teachers are surprised that students are so motivated. Students are surprised that they get to do something they feel so strongly about while at school. Parents are amazed at all the exciting things students get to do at school. Outsiders in the surrounding community are surprised when students take up space in the community and contribute. It seems to be precisely the interaction with and value creation for outsiders that is the biggest source of surprise. Adults find it unexpected to see competent children who contribute.

My own surprise has mainly been about why value creation for others is so unusual in school, and why I, as a nerdy Chalmers researcher in the Department of Entrepreneurship, am one of the few who suggest this to teachers. Especially when so many teachers agree and recognize the power of students’ value creation for others. How long have you teachers really known about this elixir of learning? And a slightly more serious question – why has such powerful learning oxygen been used so rarely in school so far?

I honestly do not know the answer to that question. Maybe the way we have chosen to organize the school has this unexpected side effect? Or is it perhaps a widespread view of children and young people as passive recipients of education and discipline instead of active and capable rocket pilots? Maybe it’s a Piaget-inspired assumption that students have not yet reached the stage of development required for them to be able to help others with something?[48] Juul (1997, p.11) writes in his book on competent children that we adults have “made a decisive mistake when we assumed that children were not real people”. Qvortrup (2009) believes that we seem to see young people in society as incompetent human becomings or not-yet-adults, and regrets a widespread view of them as unable to contribute to society before the day they got their first job.

When I ask teachers if they think that their students would be able to handle value-creating activities aimed at outsiders, I often hear that “my older students would probably be able to do it, but maybe not my younger ones”. Both primary and middle school teachers have said this. It makes me wonder if students too seldom get a fair chance to use and develop their inherent ability to create value for others here and now. To paraphrase the child psychologist Margareta Berg Brodén (1989):[49]

Perhaps we are mistaken – perhaps students are competent to create value for others.

… outside their group …

A natural start in value creation for many students is to be able to do something that helps a classmate. It probably happens quite naturally in all the classrooms in the world. According to evolutionary biologists, we are ultrasocial beings. But how often is it a conscious strategy on the part of teachers? In fact, more and more often. A phenomenon that is becoming more widespread in schools is cooperative learning. One of the recommended strategies is to make the students mutually dependent on each other in a positive way, for example by letting them need each other to succeed in something.[50] This often strengthens both learning and social ties. A kind of win-win situation.

It is worth remembering that competitions rather represent a negative interdependence, a kind of win-lose situation. When some win, others can see themselves as losers. We can not conclude that competitions work only by measuring the breadth of the winners’ smiles. I have a research colleague in the UK who has made it her most important research endeavor to strongly object to the widespread competition in education.[51] There are absolutely other ways to create interdependence than to make the majority of our students feel like real losers. Both cooperative and value creation pedagogy describe such alternative ways.

It is not easy to draw a line between cooperative and value creation pedagogy. The question is also whether it even makes sense. But I do not want to repeat here all the fine strategies that cooperative learning has developed over the years. They have also already been nicely described in many other books. So let’s pretend for the moment that some kind of boundary goes when students do something that becomes valuable to someone other than their own group or teacher.

… class…

A natural next step in value creation is to go outside one’s own class but still remain in one’s own school’s safe environment. This is probably already happening in many schools around the world. Students who help on an outdoor day, sit on the student council, hold a sports lesson or exhibit their work at a school fair. Here, value creation pedagogy can contribute with new perspectives that reinforce what is already being done. I am convinced that students can be persuaded to take much greater personal responsibility in cross-class activities.

Four simple control questions I usually ask myself when I hear a customary story about what is already being done at a school are:

· Did the activity build on a student’s own idea or passion?

· Was something done that had not been done before at that school?

· Was concrete value created for others that the student received feedback on?

· Did the students get to try and try again and learn from their mistakes?

Four simple questions taken from each of the four corners in the diamond model in Figure 6.5 in Chapter 6. With a few simple steps, what is already being done at a school can have a much stronger effect.

… or school

When students are allowed to meet people outside the school, it is usually called Collaboration school-work life or Collaboration school-world. However, this does not seem to be a particularly prioritised issue in our society. How often do study and career counselors with their hats in hand come to both teachers at their own school and representatives in working life, and ask: “Could you consider letting these students get a little knowledge of the world around them?” In school, it should not really even be an issue. Yet every year, career counselors are tirelessly heard reminding their colleagues that knowledge of the world around them is the Whole School’s (damn) responsibility. I sometimes wonder quietly, is not it the responsibility of the whole society? What happened to the saying that it takes a whole village to raise a child? Instead, it feels as if career counselors are responsible for a difficult cooperation with polite but fundamentally uninterested people.

Counselors I meet usually appreciate value creation pedagogy. Almost every year, they invite me to their big national conference where they talk about counseling issues. I have been there a few times and really felt among friends, but I rarely have anything new to tell. The seven or thirty-one words are always the same. I guess counselors like the change of focus from a distant future for the students – “What do you want to become when you grow up, little friend?” – to activities here and now where students can create value for others outside the school. I also think they like the change of perspective. Instead of the outside world creating value for the students through the usual study visits, school visits and fairs, the students create value for the outside world in thousands of different ways. There is probably no more powerful way to get a feel for a future profession than to take action and try it out in practice here and now.

There are many school activities that are almost value-creating, but that stumble on the finishing line in collaboration with outsiders. A blog no one reads, a job interview where no one is to be hired, a student parliament where no real decisions are made or an exhibition where visitors only come to be nice. Students are certainly not stupid. They quickly see through an activity that is not meaningful. But they play along, especially if it is to be assessed. However, we adults can do better.

I am often struck by how small the piece of the puzzle is that needs to be added to reach much further. Do exactly what you are already doing, but add a challenge to the students to try to create concrete value for those you still intended to meet outside of school. Students often have hundreds of ideas if they get the chance to brainstorm, and it does not matter if they fail. It is the attempt that counts. Think sandwich in Madrid.

Something that is also often missed is how much students can achieve when all three launchers are full of learning oxygen. An entire class that goes to great lengths to make a difference can build up extensive knowledge in an area in just a few months.

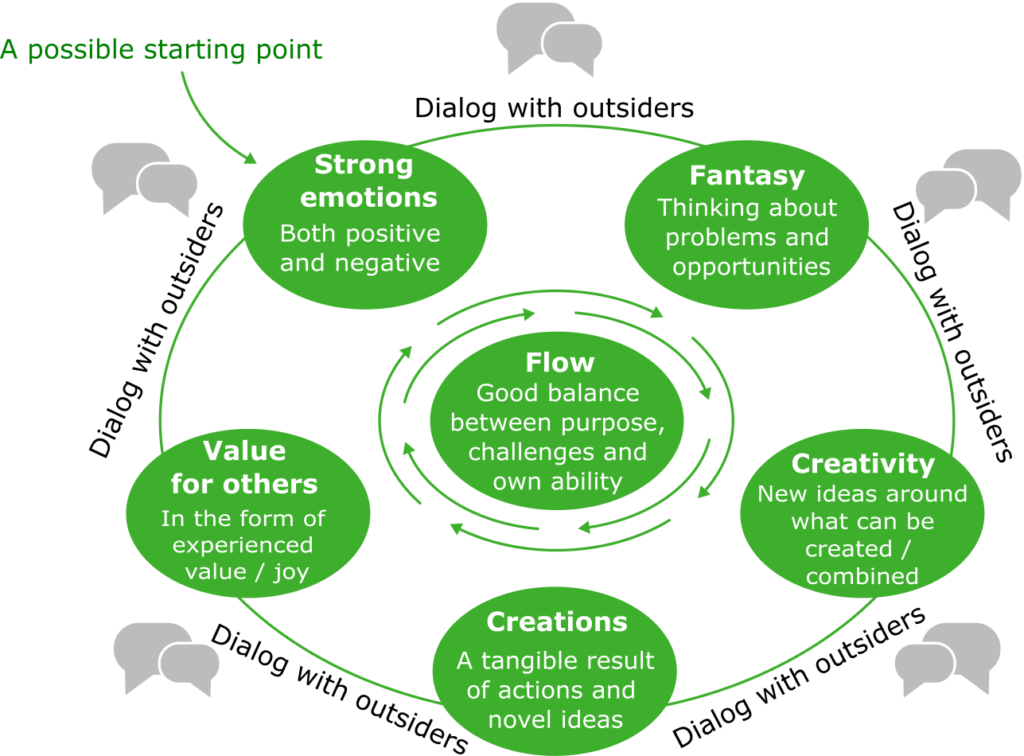

A circular process of immersive flow

Now it’s time to put all the words and phrases together into a whole. It is not an easy task. There is a risk that it will be a simplification that does not capture the full magnitude of the phenomenon. But Figure 1.6 nevertheless shows a circular process that includes much of what I have just described.

Figure 1.6 value creation pedagogy illustrated as a circular process of flow.

A good starting point is strong emotions. Few things can trigger our imagination and creativity as much as emotions. Hopefully, the fantasizing then leads to some form of creation, a concrete result, perhaps a prototype or an experience that can be tested on outsiders. Did it become valuable? What did they think? When students receive much sought-after feedback from outsiders, we again get strong emotions that trigger new imagination, creativity and new creations. Then it goes around, round after round. Throughout the circular process, students continuously gain new energy and motivation through constant dialogue with the outside world. Emotions are aired with outsiders, ideas are tested, creations are displayed, values are created.

Hopefully, the process is also characterized by flow, defined by creativity researcher Csíkszentmihályi as a good balance between challenges and one’s own ability.[52] In that case, students occasionally lose track of time. They start doing school work during breaks, voluntarily. When that happens, we know we’ve got them into flow. Then nothing can stop them from learning in-depth.

References

Axelrod, R., & Hamilton, WD (1981). The evolution of cooperation. Science, 211(4489), 1390-1396.

Batson, CD, Ahmad, N., Powell, AA, & Stocks, E. (2008). Prosocial motivation. In J. Shah & W. Gardner (Eds.), Handbook of motivation science New York City: Guilford Publications. pp. 135-149.

Batson, CD, & Shaw, LL (1991). Evidence for altruism: Toward a pluralism of prosocial motives. Psychological Inquiry, 2(2), 107-122.

Baumeister, RF, Vohs, KD, Aaker, JL, & Garbinsky, EN (2013). Some Key Differences Between a Happy Life and a Meaningful Life. Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(6), 505-516.

Berg Brodén, M. (1989). Mother and child in no man’s land. Stockholm: Liber AB.

Berg, L. (2005). Dawn of the Kalahari: How Man Became Human. Stockholm: Ordfront.

Blenker, P., Korsgaard, S., Neergaard, H., & Thrane, C. (2011). The questions we care about: paradigms and progression in entrepreneurship education. Industry and Higher Education, 25(6), 417-427.

Boltanski, L., & Thévenot, L. (2006). On justification: Economies of worth. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Boud, D., Cohen, R., & Walker, D. (1993). Using experience for learning. Berkshire: McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

Bregman, R. (2020). Humankind: A hopeful history (Swedish title: Basically good): Bloomsbury Publishing.

Brentnall, C., Rodríguez, ID, & Culkin, N. (2018). The contribution of realist evaluation to critical analysis of the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education competitions. Industry and Higher Education, 0950422218807499.

Bruyat, C. (1993). Business creation: epistemological contributions and modeling. Doctoral thesis, Pierre Mendès-France-Grenoble II University,

Bruyat, C., & Julien, P.-A. (2001). Defining the field of research in entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(2), 165-180.

Costanza, R., Fisher, B., Ali, S., Beer, C., Bond, L., Boumans, R., Danigelis, NL, Dickinson, J., Elliott, C., & Farley, J. ( 2007). Quality of life: An approach integrating opportunities, human needs, and subjective well-being. Ecological Economics, 61(2), 267-276.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2008). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York, NY: Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

Cuban, L. (2007). Hugging the Middle: Teaching in an Era of Testing and Accountability, 1980-2005. Education policy analysis archives, 15(1), 1-29.

D’Mello, S., Lehman, B., Pekrun, R., & Graesser, A. (2012). Confusion can be beneficial for learning. Learning and instruction.

Dewey, J. (1939). Theory of valuation. In O. Neurath, R. Carnap, & CW Morris (Eds.), International encyclopedia of unified science Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. pp. 1-67.

Egan, K. (2002). Getting it wrong from the beginning: Our progressivist inheritance from Herbert Spencer, John Dewey, and Jean Piaget. London: Yale University Press.

Engeström, Y. (1999). Activity theory and individual and social transformation In Y. Engeström, R. Miettinen, & R.-L. Punamäki (Eds.), Perspectives on activity theory Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Fayolle, A. (2007). Entrepreneurship and new value creation: the dynamic of the entrepreneurial process. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Feldman, DB, & Snyder, CR (2005). Hope and the meaningful life: Theoretical and empirical associations between goal – directed thinking and life meaning. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24(3), 401-421.

Fiske, ST (2008). Core Social Motivations – Views from the Couch, Consciousness, Classroom, Computers, and Collectives. In J. Shah & W. Gardner (Eds.), Handbook of motivation science New York, NY: Guilford Press. pp. 3-22.

Fohlin, N., Moerkerken, A., Westman, L., & Wilson, J. (2017). Basic book in cooperative learning: the path to the collaborative classroom. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Frankl, VE (1985). Man’s search for meaning. New York City: Simon and Schuster.

Goss, D. (2005). Schumpeter’s legacy? Interaction and emotions in the sociology of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(2), 205-218.

Graeber, D. (2001). Toward an anthropological theory of value: The false coin of our own dreams: Springer.

Gärdenfors, P. (2006). The meaning-seeking man. Stockholm: Nature and culture.

Harari, IN (2015). Sapiens: a brief history of humanity: Nature & culture.

Hattie, J. (2011). Visible Learning For Teachers: Maximizing Impact On Learning. London: Routledge

Helgesson, C.-F., & Muniesa, F. (2013). For what it’s worth: An introduction to valuation studies. Valuation Studies, 1(1), 1-10.

Hoff, E. (2010). Playful children become creative adults. Cross-section – on humanities and social science research, 3(10), 14-17.

IBM. (2010). Capitalizing on complexity: Insights from the Global Chief Executive Officer Study. Somers, NY: IBM Institute for Business Value

Jarvis, P. (2006). Towards a comprehensive theory of human learning. New York, NY: Routledge.

Jonassen, DH, & Land, SM (2000). Theoretical foundations of learning environments. London, UK: Routledge.

Jones, C. (2011). Teaching entrepreneurship to undergraduates. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

Juul, J. (1997). Your competent child: on the way to new values for the family. Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand.

Labaree, DF (2005). Progressivism, schools and schools of education: An American romance. Paedagogica historica, 41(1-2), 275-288.

Lackéus, M. (2013). Developing Entrepreneurial Competencies – An Action-Based Approach and Classification in Education. Licentiate Thesis, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg. (ISSN: 1654-9732)

Lackéus, M. (2016). Value creation as educational practice – towards a new educational philosophy grounded in entrepreneurship? Doctoral thesis, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden. (ISBN 978-91-7597-387-6)

Lackéus, M. (2017). Does entrepreneurial education trigger more or less neoliberalism in education? Education + Training, 59(6), 635-650.

Lackéus, M. (2018). “What is value?” – A framework for analyzing and facilitating entrepreneurial value creation. Uniped, 41(1), 10-28.

Lackéus, M. (2021). The science teacher – a handbook for research in school and preschool. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Lackéus, M., Lundqvist, M., & Williams Middleton, K. (2016). Bridging the traditional – progressive education rift through entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 22(6), 777-803.

Lindström, L. (2006). Creativity: What is it? Can you assess it? Can it be taught? International Journal of Art & Design Education, 25(1).

Lucas, B., & Venckute, M. (2020). Creativity – a transversal skill for lifelong learning. An overview of existing concepts and practices: Literature review report. Seville: Joint Research Center, European Commission

McClelland, DC (1967). The achieving society (Vol. 92051): Simon and Schuster.

Metz, T. (2009). Happiness and Meaningfulness: Some Key Differences. In L. Bortolotti (Ed.), Philosophy and Happiness Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave MacMillan. pp. 3-20.

Mulligan, J. (1993). Activating internal processes in experiential learning. Using experience for learning, 46-58.

Neuberg, SL, & Schaller, M. (2013). Evolutionary social cognition. In Oxford handbook of social cognition. pp. 656-679.

OECD. (2019). OECD Future of Education and Skills 2030: OECD Learning compass 2030. Paris: OECD

Postle, D. (1993). Putting the heart back into learning. In D. Boud, R. Cohen, & D. Walker (Eds.), Using experience for learning London: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press. pp. 33–45.

Qvortrup, J. (2009). Are children human beings or human enjoings? A critical assessment of outcome thinking. Rivista Internazionale di Scienze Sociali, 631-653.

Ramberg de Ruyter, J. (2016). The crucial creativity. Master’s thesis, Linköping University,

Reid, A., & Petocz, P. (2004). Learning domains and the process of creativity. Australian Educational Researcher, 31, 45-62.

Rizzo, KM, Schiffrin, HH, & Liss, M. (2013). Insight into the parenthood paradox: Mental health outcomes of intensive mothering. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(5), 614-620.

Seligman, ME (2012). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York City: Simon and Schuster.

Shernoff, DJ, Csikszentmihalyi, M., Shneider, B., & Shernoff, ES (2003). Student engagement in high school classrooms from the perspective of flow theory. School Psychology Quarterly, 18(2), 158.

Sheth, JN, Newman, BI, & Gross, BL (1991). Why we buy what we buy: a theory of consumption values. Journal of business research, 22(2), 159-170.

Smith, PL, & Ragan, TJ (1999). Instructional design: Merrill Upper Saddle River, New Jersey.

Stark, D. (2011). The sense of dissonance: Accounts of worth in economic life. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Strandberg, L. (2009). Vygotsky in practice: Among stud horses and cheats. Stockholm: Norstedts.

Tomasello, M. (2014). The ultra ‐ social animal. European Journal of Social Psychology, 44(3), 187-194.

United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York: United Nations

Vestergaard, L., Moberg, K., & Jørgensen, C. (2012). Impact of entrepreneurship education in Denmark – 2011. Odense, Denmark: The Danish Foundation for Entrepreneurship – Young Enterprise

Wittgenstein, L. (2010). Philosophical investigations: John Wiley & Sons.

Zahidi, S., Ratcheva, V., Hingel, G., & Brown, S. (2020). The future of jobs. Geneva, Switzerland: World Economic Forum

[1] Freely translated from Wittgenstein (2010).

[2] See Blenker et al. (2011), Jones (2011) and Vestergaard, Moberg and Jørgensen (2012). There is also closely related literature that deals with entrepreneurship as value creation, mainly Bruyat (1993), Bruyat and Julien (2001) and Fayolle (2007).

[3] See Lackéus (2013).

[4] See Lackéus (2016, 2017).

[5] See Gärdenfors (2006) and Frankl (1985).

[6] See Rizzo, Schiffrin and Liss (2013). See also Baumeister et al. (2013, p.511).

[7] See Baumeister et al. (2013) and Metz (2009).

[8] See Lackéus, Lundqvist and Williams Middleton (2016).

[9] Read more about traditional versus progressive education in Labaree (2005) and Cuban (2007).

[10] See Lackéus (2016, p.53) and Lackéus, Lundqvist and Williams Middleton (2016, p.790).

[11] Dewey (1939) has very wisely written about this in his book on value.

[12] Read more about the important role so-called prior knowledge plays in e.g. Hattie (2011, p.25) and Jonassen and Land (2000, p.14).

[13] Read about this in Smith and Ragan (1999, p.27).

[14] My favorite text is his book Towards a comprehensive theory of human learning (Jarvis 2006).

[15] See, for example, Shernoff et al. (2003).

[16] See Csíkszentmihályi (2008, p.74).

[17] See, for example, D’Mello et al. (2012) who writes about how confusion can strengthen learning.

[18] See Berg (2005, p.144-186) and Harari (2015, p.83-120).

[19] See Berg (2005, p.206).

[20] Read more about human creative joy in Goss (2005), Metz (2009) and Feldman and Snyder (2005).

[21] For an overview of Vygotsky and his Russian successors, see Engeström (1999). See also Strandberg (2009).

[22] See, for example, the definition of creativity in Reid and Petocz (2004).

[23] See OECD (2019), Zahidi et al. (2020) and IBM (2010).

[24] Metz writes about this (2009, p.8).

[25] See Lindström (2006) who writes about difficulties in incorporating creativity in school.

[26] For an in-depth look at what inhibits creativity, see Ramberg de Ruyter (2016).

[27] Ramberg de Ruyter (2016, p.39 and 47) describes how the National Agency for Education and the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise see it as trying to dissolve the dichotomy between knowledge and creativity.

[28] According to Lucas and Venckute (2020).

[29] See Boud, Cohen and Walker (1993), especially Mulligan (1993) and Postle (1993).

[30] Read more about different perspectives on children’s creativity in Hoff (2010).

[31] See, for example, Graeber (2001), Stark (2011), Dewey (1939), Boltanski and Thévenot (2006) and Helgesson and Muniesa (2013). Texts by me, see mainly Lackéus (2016, p.11-19; 2018; 2021, p.35-46).

[32] This review is a brief summary of an article by Lackéus (2018). See also Lackéus (2017) for an in-depth reasoning about value for oneself versus value for others.

[33] Read more about this in Seligman (2012) and Costanza et al. (2007).

[34] Read more about the “flow theory” in Csíkszentmihályi (2008).

[35] Read more about this in Fiske (2008) and in McClelland (1967).

[36] See Baumeister et al. (2013).

[37] For more information, see Boltanski and Thévenot (2006).

[38] Read more about conditional value in Sheth, Newman and Gross (1991).

[39] They are described in the United Nations (2015).

[40] See Batson and Shaw (1991).

[41] According to Bregman (2020, p.232-234), many see themselves as helpful but others as selfish.

[42] According to Berg (2005, p.265).

[43] This is the basic thesis in Bregman’s (2020) book about man as basically good.

[44] See, for example, Neuberg and Schaller (2013) and Tomasello (2014).

[45] Read more about this in Batson and Shaw (1991) and in Batson et al. (2008).

[46] See Neuberg and Schaller (2013, p.25).

[47] See Axelrod and Hamilton (1981, p.1393).

[48] Piaget’s work with children’s developmental stages has had a great impact on pedagogy during the 20th century, but in recent years has begun to be increasingly questioned, see Egan (2002).

[49] Berg Brodén’s phrase “Perhaps we have made a mistake – perhaps children are competent” was quoted in the introduction to Juul’s (1997) book Your competent child as an important source of inspiration.

[50] See Fohlin et al. (2017, pp.115-130).

[51] The colleague’s name is Catherine Brentnall, see for example Brentnall, Rodriguez and Culkin (2018).

[52] Se Csíkszentmihályi (2008).