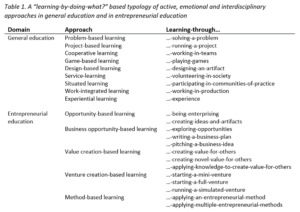

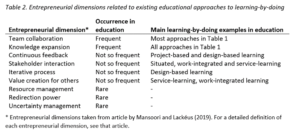

Now let’s talk effects. Because if there is anything that motivates work with value creation pedagogy, it is all the strong effects we have been able to see when students and teachers work with value creation. Students gain strengthened motivation, self-confidence, perseverance, initiative and empathy for others. They become kinder to each other, take greater responsibility for their learning and experience school as more meaningful. Many students also learn more and get higher grades. The effects are mainly triggered by interaction with the outside world, value creation for others, teamwork and receiving feedback from outsiders, see Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 Effects and how they arise in value creation pedagogy (Lackéus 2020).

Teachers also get a better situation. They get safer classes, easier assessment, stronger inclusion through more varied teaching and increased clarity in student learning. They then avoid spending so much time motivating students and dealing with conflicts between students. The teaching profession also becomes more fun.

All this sounds almost too good to be true. So a question that arises is: “How do you know this, Martin?” So let me take it from the beginning.

Ten years of research on value creation pedagogy

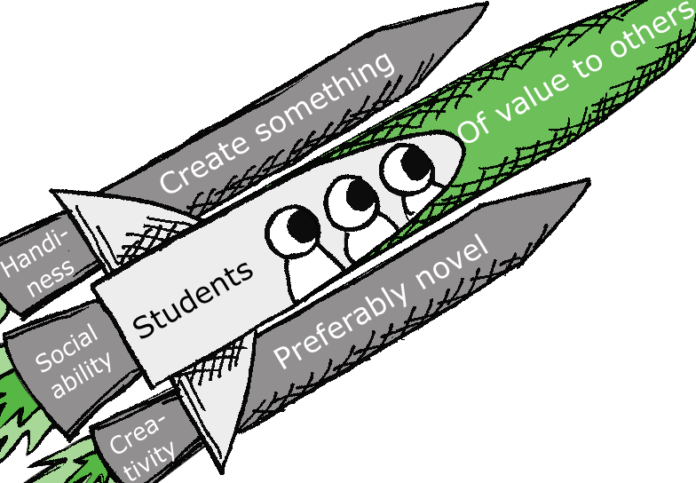

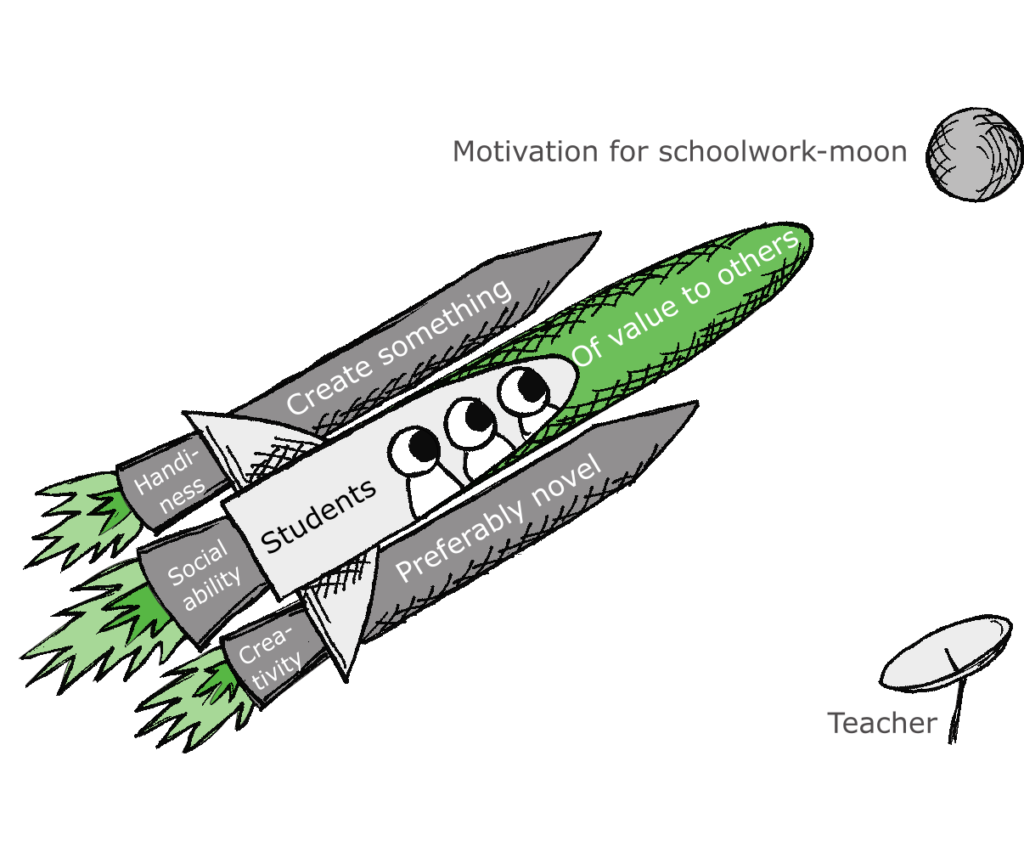

I am a kind of backwards researcher. Most researchers start with a theoretical idea, set up a hypothesis and then test whether it holds in practice. I instead started with a vague but extremely strong feeling in my stomach that something worked really well in practice. The question was never whether it worked, but instead what it was that worked, and why. A kind of appreciative inquiry.[1] My life had taken an unexpected turn when at the age of 26 at Chalmers I was thrown into a crazy space rocket full of learning oxygen. For me, the effects were crystal clear, emotional and life-changing. He who has lived on the moon himself does not have to doubt its existence. So that this was an educational effort that worked, I already knew that when I started my research ten years later on what the teachers did with us. But what, of everything I had been through, was it that worked? And why did it work? It would take another ten years to come up with well-grounded answers to these questions.

To get answers, I started by doing interviews. Lots of interviews. I sat and listened for hundreds of hours to students who were now in the same emotional situation as I had been twelve years earlier. They went to the same education that I myself had attended. I asked them in different ways what caused emotional storms in them, and why. Between interviews, I asked them to write down their thoughts each time they experienced a new emotional event on our programme and send the text to me. A kind of emotional survey. My own emotional roller-coaster from the same education told me that it was among the emotions I should look for answers.

The emotions gave the answer to what worked

And quite rightly, it was precisely among all those emotions that I found the answer to the “what” question. The students became most emotionally involved when they got to do something that became valuable to someone external. The pattern was unexpected but very clear. Previously, researchers had thought that it was the start-up of a new venture that caused the strongest effects, much like the concept of Young Enterprise has its focus. But here I found a completely different explanation. In the summer of 2013, I wrote in my first completely own research article that teachers could benefit from exposing their students to value-creating activities.[2] Since then, there have been many different texts on the same theme, some of which have been reviewed and published scientifically.

After finding the answer to what it was that made the strongest difference, I went on to study in more detail what students’ value creation led to for themselves. Such research is called doing an impact study. What effects could we observe when pupils and students learned by creating value for others? When, how and why did the effects occur? Me and my new Chalmers colleague Carin Sävetun spent seven years studying these questions. The first sub-study began in 2013 and the fifth and final one ended in 2017. Then it took a few years to analyze all the empirical material as well. Carin managed to change jobs and is today the CEO of the small IT company we needed to start to build our most important tool for data collection, an app for emotion surveys that we named Loopme. During the trip, we received help from director of education Ragnar Åsbrink at the National Agency for Education, who was very interested in our research. The research article summarizing our conclusions from 291 interviews and 10,953 emotional questionnaire responses from 1,048 participants in 35 different schools was published in 2020.[3]

From 3,500 to twenty-five pages in two years

The conclusions were so unexpected and different from previous research that the scientific review of the article took two years and involved eight researchers around the world. We got to know the names of two of them, the rest were doubly anonymous. They did not know who we were and we did not know who they were, other than that several of them were very prominent. Our dialogue had to take place in writing and eventually filled about sixty pages of text. With such controversial conclusions, the expert reviewers were extra careful. Therefore, the months passed and became years. The article also got better and better for each duel. A key question was how the extensive data we collected and which proved the effects would be presented so it became both credible and understandable. How to summarize 3,500 pages of interview text and 10,953 questionnaire responses on twenty-five meager pages? We scratched our heads for a long time about this.

Finally, the Danish professor Helle Neergaard gave us crucial advice. She suggested that we do what she called mega-tables with both the effects and many illustrative quotes from students in one and the same table. In this way, we were able to let our collected data speak for us, and convince the experts that the effects we described were not free fantasies. For me, this became an emotional moment of deep insight and learning. Helle solved our communicative dilemma in an elegant way. Without that advice, we might not even have had our overall results published. That’s why I also remember exactly where I sat when I received the advice. Where, do you think? Yes, in Madrid of course. Another Spanish bocadillo moment.

The final article contains two different mega-tables that describe the effects we saw. The article can be downloaded for free thanks to Chalmers buying it free from download fees.[4] Search for “comparing impact Lackéus” and you will find it easily.

Effects on students

Let me now briefly summarize what one of the mega-tables says about the effects of value creation pedagogy, see Table 2.2 below.

Table 2.2 Effects of value creation pedagogy (Lackéus 2020, p.951).

Interaction with the outside world has strong effects on students. Their self-confidence is strengthened when they notice that they receive a more positive response than they had expected. Their ability to take initiative is strengthened when they discover that the outside world is not waiting for or cares about the one who does nothing. They must act here and now to get their coveted feedback from outsiders. Their communicative ability is strengthened when they feel the pressure to make a good impression and get their message across.

The very act of creating value for others usually results in extremely strong motivation. It is perceived as fun, exciting, meaningful and rewarding. If the value creation is based on knowledge, the students’ knowledge development is also strengthened. Knowledge then becomes an indispensable means of achieving the goal of creating value for others. Speaking of confusion between goals and means (see Chapter 1), we see the opposite here compared to the teachers’ situation. Over time, we also often see identity changes. Many students increasingly define themselves as such a person who creates value for others. They do not express it with those words, but the meaning revolves around empathy and joy of being able to do something meaningful with and for others.

Being able to work in teams differs here from more traditional group work where tasks are often divided up and performed mainly individually or in small groups within the group. With an outside recipient of value, it becomes more like teamwork for real, and students benefit more from each other’s different skills, strengths and interests. This in turn leads to them learning new things about themselves. They compare their own strengths, weaknesses, priorities and values with others in the team.

Applying theories and knowledge in practical value creation for others strengthens the development of knowledge. A deeper understanding is developed and students remember better what they have learned. It may sound obvious, but such a bridge between theory and practice occurs more naturally in value-creating processes than otherwise.[5]

With outside recipients of value as an unpredictable joker in the game, the learning processes become more uncertain than before. It is not possible to know in advance how an outsider will perceive and react to the students’ attempts to create value. It develops students’ courage and perseverance. Because when they dare and succeed, many students usually say that this was actually not as dangerous as they first thought. The outcome does not always turn out as planned, but then they try again and discover that perseverance pays off. Just like I gradually learned to order a sandwich in Madrid.

When students finally get that much-coveted feedback from outsiders, it leads to a powerful increase in motivation. This is probably the biggest source of motivation in the whole process. Therefore, outsiders’ feedback on the value created (or not) is absolutely crucial. Perhaps here we have the cleanest rocket fuel of all for students’ learning. Self-confidence also tends to skyrocket when students succeed in creating something of value, and it is again the feedback that is the proof that they have succeeded. Students often mention in particular that they see feedback from others as clear proof that they have succeeded. It’s almost like a trophy crowning success.

Negative feedback also provides motivation and learning

Negative feedback and criticism can also strengthen students’ motivation and learning, because then the students feel that they have influenced others and made a difference. Dismissive feedback can also give them energy to try again. A well-documented example is from 2016 when two students at Edboskolan in Huddinge wrote a blog post about how they saw value creation pedagogy as a new era for the school (Sandén and Jonsson 2016). The post was heavily criticized by principals and teachers on Twitter. Many insinuated that the students had been indoctrinated. The teacher Maria Wiman (2019, p.147-148) describes in her book on value creation pedagogy how the criticism was received by the students:

“The students were appalled and upset, absolutely! But above all, it was exciting! […] When I look back on what happened, there is no doubt that the students came out of this strengthened. They stood up for their cause and for each other.”

The students themselves expressed that the event strengthened their motivation, perseverance, communicative ability, initiative and knowledge of online hate. They also wrote more texts about what society can learn from the fact that some adults are not able to cope with competent students who contribute. The student Ludwig Berglind wrote in a debate post in the local newspaper:[6]

“Maybe you are someone who thinks that children are stupid? […] We are not stupid. We are the future. Children make a difference.”

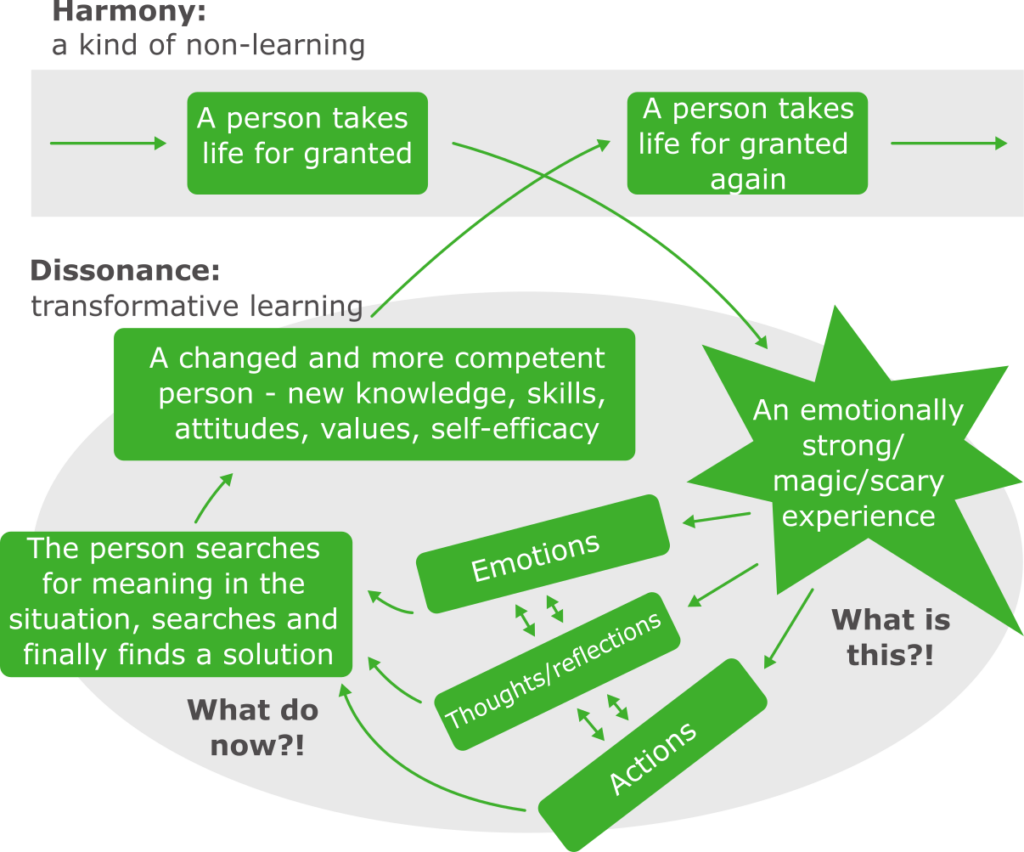

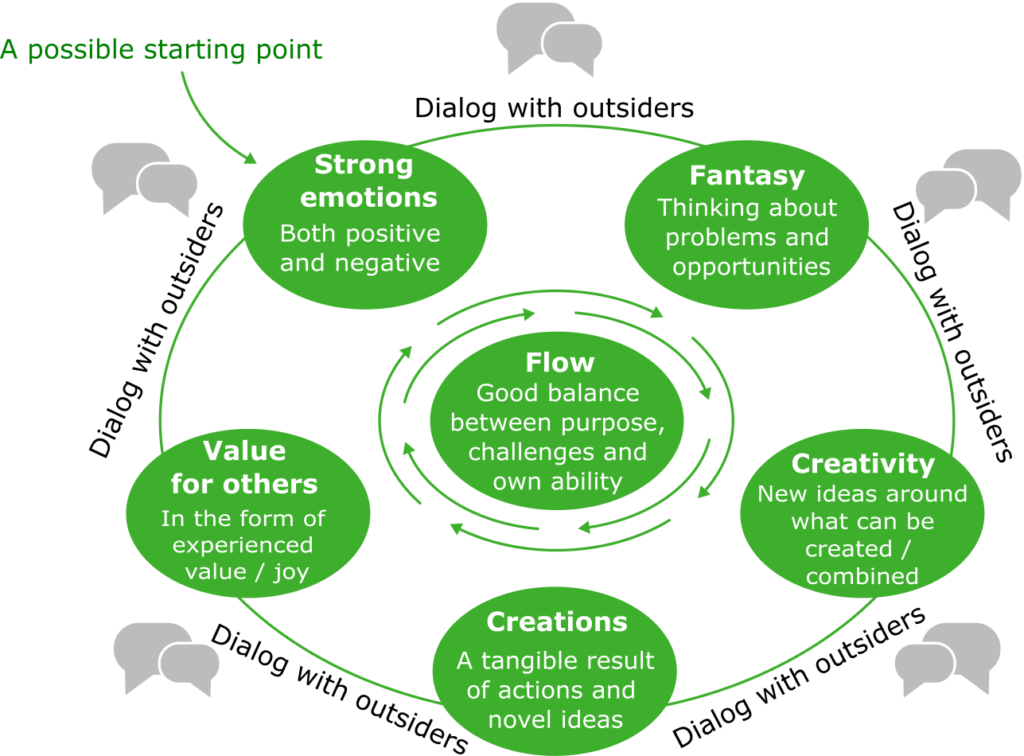

I am not at all surprised by the powerful and continued learning from an initially unsuccessful attempt to create value for others. We see the same effect every year among our students at Chalmers. In a recent thesis I supervised, two of my students explored what people learn from negative events.[7] They interviewed sixteen of our alumni about their most emotional failures while they were students with us, and asked what they had brought with them in life. It was a nice illustration of how incredibly much we learn from failures and difficulties, see figure 2.2. We learn the most about ourselves and our team. But we also learn about problem solving, communication, value creation, social skills and being entrepreneurial. I think Jarvis is probably right that harmony is a non-learning situation. In any case, there will not be nearly as strong learning in a purely harmonious classroom alone. If we want to get knowledge and abilities to be burned into the students’ brains for life, we should thus strive for emotional highs and lows. A good way to succeed in this is value creation pedagogy.

Figure 2.2 Common types of learning from failures (Blomé and Simson 2021).

Factors that affect the strength of the effects

If we now for a while again see value creation pedagogy as the accelerator in a kind of educational electric car, it would be good if we could adjust the speed a little. When practicing driving in a parking lot, it may be directly inappropriate to push the accelerator pedal into the carpet. In our research, we have seen seven factors that affect how strong the effects will be on the students, but also how challenging it will be for the teacher. For those who want maximum speed, the seven factors can be used to increase speed. For those who want to try on a small scale, some factors can be adapted in the other direction. The seven factors are shown in Figure 2.4 and are now briefly described.

Figure 2.4 Progression model with seven factors that affect the strength of the effects of value creation pedagogy (Lackéus and Sävetun 2016).

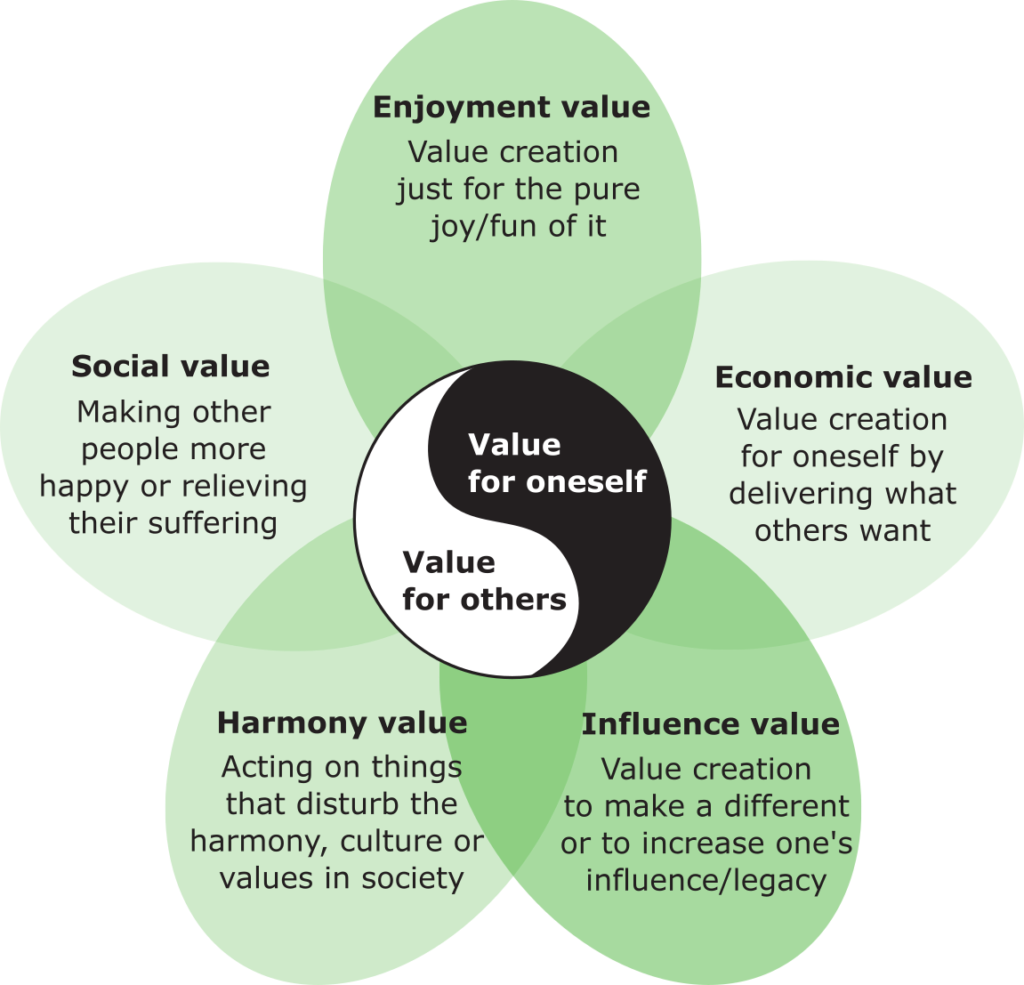

Kind of value. The kind of value that has the strongest effect on students has proven to be influencel value. Many students love to be able to influence other people in depth. If you want a soft start, you can instead focus on creating enjoyment value and social value. Economic value creation can work well, but is associated with some challenges. Managing money in school can be complicated. It can also be perceived as a bit too capitalist and self-centered. An alternative is to raise money for charity, read more about it in Chapter 5.

Recipient. Varying the type of recipient of value is one of the most important ways to control the degree of complexity and impact. Staying within the school’s safe confines is easier for teachers and can be a good start, but does not have as strong effects on students.

Feedback. The type of feedback from outsiders affects how committed the students become. The strongest effect is when the students feel and get proof that they have made a big concrete difference for many people. At the same time, it is also the most difficult level to reach in practical terms.

Magnitude. Small projects in small groups are easy to manage. However, we see the strongest effects when value creation takes place in large projects in the whole class. Then the students usually need to be divided into different groups based on different competences and tasks, just like in working life.

Time span. The longer a value-creating activity lasts, the stronger the effects on the students often become. Here, calendar time is more important than the number of hours in the classroom. The projects with the strongest effect on students have often lasted for a year.

Planning. Thoughtful planning increases the time required for teachers, but has stronger effects on students. However, good planning does not have to involve a large scale. A metaphor many teachers find useful is to see value creation pedagogy as a drop of colour you pour into a glass of water. The value-creating element is small but recurring, and then colours all teaching with a sense of meaning that strengthens students’ learning.

IT support. Sophisticated pedagogical forms of work require sophisticated methods and tools that support teachers. IT support can be used to handle the complexity of learning for assessment, follow-up and dialogue.[8] We return to this in Chapter 8 on assessment as jazz. IT support can also be used in students’ interactions with outsiders. It can be through blogs, social media, video conferencing, programming or other digital solutions. An interesting digital platform used in Sweden to publish students’ texts is Mobile Stories, and can be said to be the contemporary equivalent of the French educational philosopher Freinet’s printing press.[9]

Why do the effects occur?

Now let’s take an overall perspective for a moment. How can we understand the altruistic paradox that students seem to be more motivated to create value for others in ten minutes than for themselves in ten years?[10] At the risk of making phlogiston-like claims, I will nevertheless attempt a more comprehensive explanation here. I think there is a perspective – meaningful action – that can help us understand both how the school works today and how it could work better with more widespread value creation activities among students. Everything boils down to a kind of axiom, a general and universal consideration by philosophers Ludwig von Mises and Michael Oakeshott. They wrote independently that all human actions are always meaningful from the individual’s perspective.[11] Applied to school, students thus have meaningful reasons to deviate from school, based on their own narrow perspectives. They probably see the school as meaningless. It could be the whole purpose they experience as meaningless – to learn things they see no use for in their lives as they live here and now.

When we then add a purpose for the school that is so different as to create value for others, it has a great impact. On the one hand, there is of course a risk of purpose competition. Should we no longer focus on learning in school? But it also opens up completely new possibilities. With a new purpose available, teachers can better reach those students for whom the existing purpose does not work. A new basic purpose starts a long chain reaction in us humans. It triggers deep emotions, it affects what meaning we see with what we do and thus basically what learning is possible.[12] Instead of saying that the two purposes compete with each other, we can see them as complementary. One purpose captures the present and the other purpose captures the future.

When we appeal to truant students to return to school, we often do so today by appealing to their hedonistic and selfish side – come back so you can enjoy the good life and avoid a lot of suffering as you get older. Value creation gives us access to a completely different and more prosocial strategy – come back and be part of a warm community where we make a difference for others for real, here and now.

The effects we see cannot be understood incrementally. One plus one purpose here is far more than two. We may need to use chemical rather than mechanistic explanatory models to understand why we see the effects we see.[13] Value creation pedagogy seems to be a bit of a catalyst for school. The purpose of learning and the purpose of value creation reinforce each other. When the coloured value-creation drop hits the water surface of learning, a violent chemical reaction takes place that I honestly can not really explain the power of. What exactly is the equivalent of the piece of ceramic or metal found in a petrol car’s catalyst for exhaust gas purification?

Maybe it’s the effects of a mental time travel we see. When students’ learning becomes valuable for others here and now, and thus also for themselves, their future is connected with their present in their heads. In the film Back to the Future, lightning strikes, slams and burns the tires just at the crucial moment when Doc’s sports car converted to a time machine reaches a speed of 88 miles per hour and the time window opens. Maybe the power of value creation pedagogy comes from giving students a glimpse of their own future? Is that perhaps why study counsellors like this way of working so much?

Effects for teachers

Now we return to teachers’ everyday lives. Teachers who provide value-creating tasks to their students can also do better themselves. It’s like the saying goes: doing well by doing good. In our effect studies, many teachers have told us and written to us about exactly this. It is fun for teachers when students think school is fun and meaningful, especially if it does not happen at the cost of learning but instead strengthens learning. Then teachers’ everyday lives also become more meaningful. Many teachers think it’s nice not to have to answer the question “Why do we do this?” as often. Teachers also get more chances to assess students when more creations are made that can be assessed. In addition, the assessment becomes more inclusive when more students can show what they are capable of.

Teachers have also said that they like the increased clarity, structure and guidelines compared to other student-oriented pedagogical approaches that are often perceived as fuzzy and difficult to assess. A teacher wrote to us that value creation is a kind of middle ground between a more traditional teacher-centered teaching and student-centered but fuzzy teaching:

“It feels like value creation ends up in the middle between these two educational philosophies and specifies relatively well how I want my teaching role to develop. It uses the best of both worlds and strives to make students both involved and engaged, but at the same time contains tools for teachers to help students.”

A kind of music guiding teachers ‘and students’ movements

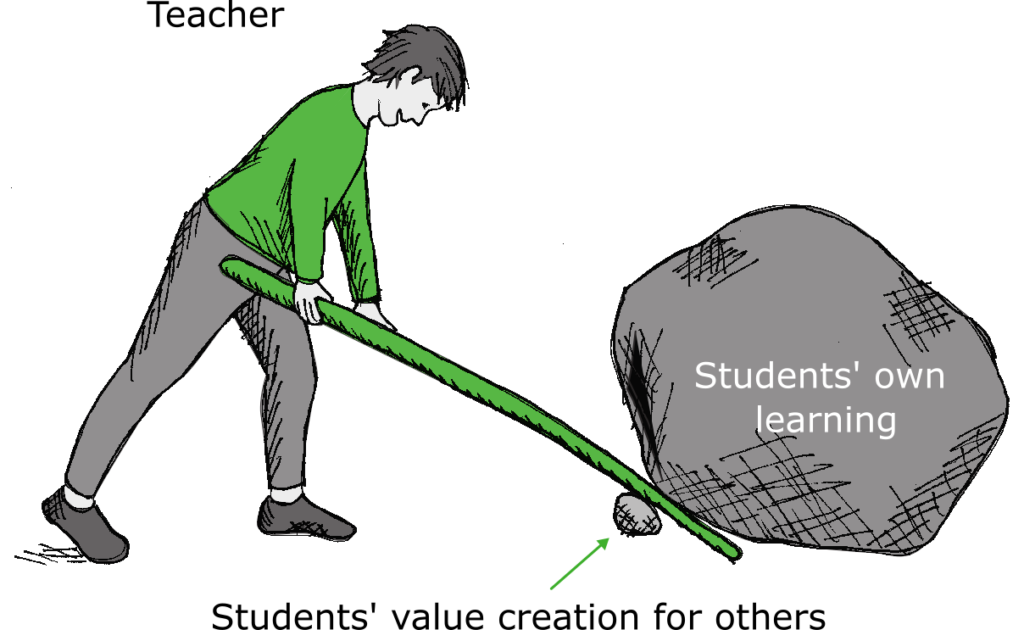

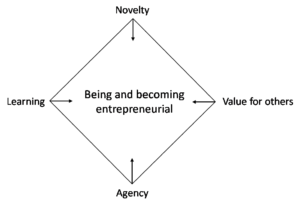

The quote above about combining two worlds captures something important with value creation pedagogy. Teachers can get help with pedagogical variation – an important but often difficult balancing act between widely differing learning philosophies. Teaching with well-balanced variation becomes more inclusive, as different students have different needs. On the front of my dissertation, I drew a figure that illustrates just this, see figure 2.5.

Figure 2.5 Value creation pedagogy as a kind of music that facilitates teachers ‘and students’ coordinated movements across the philosophical playing field of education (Lackéus, 2016, p.69).

The reclining eight in the figure illustrates a coordinated movement over the entire philosophical playing field of education. The notes are an attempt to capture that value creation pedagogy can be seen as a kind of music that teachers and students can dance to, so that they can more easily move together in a movement pattern otherwise very difficult to coordinate. Maybe it’s jazz music they dance to, see more in chapter 8.

The work begins at the bottom center of the figure with the question “For whom is this knowledge valuable today?”. Then there is a movement diagonally upwards to the left towards traditional education where knowledge is obtained through lectures, books and own work. Then the journey continues to the right towards progressive education, with students who, based on their knowledge, can try to create something of value in creative group exercises in the classroom. In the next step, students leave the classroom, either physically or digitally, and begin searching for one or more perceived outside recipients of value to their creations. Here it gets really emotional. Students make one or more attempts to really create the intended value. Then they return to the classroom and ask themselves “For whom was this knowledge valuable today?”. After reflecting and reconnecting to the knowledge material, the students take a new turn with new material, and then another.

School in good balance between theory and practice

The reclining eight in the figure shows how the value-creating process gives teachers support in issues such as when it is time for teacher-led lectures and student exercises, when creative creation should take over, when students should leave the classroom and try their wings, under their own responsibility but with a crystal clear purpose, and when it’s time to gather for reflective learning in the classroom. These widely differing approaches are also better linked together through a clear process with an engaging and concrete purpose.

When teachers and students then move in a more coordinated way across the philosophical playing field of education, they also get a better balance in everyday life between widely differing perspectives. Instead of us adults digging into the usual trenches of traditional versus progressive education, our students get a school day with a good balance between theoretical knowledge and practical application, between deep learning and emotional engagement.

Journalists who dig… trenches

Once I wrote a debate article about the balancing effect of value creation pedagogy on schools and the need for a more balanced school policy.[14] I wrote that a strong focus on student discipline but no focus on student motivation can hurt those students who are particularly dependent on intrinsic motivation. Especially then newly arrived refugees, students in socially disadvantaged areas, students with diagnoses and boys. I spiced it up with many references, because I am far from alone in having seen challenges with a lack of school motivation among certain vulnerable student groups.[15]

The article was included in a reputable daily newspaper, but I received much resistance. Promoting a balanced school turned out to be unexpectedly controversial. Maybe it was because the editor chose a rather unbalanced headline: “High demands and discipline in school risk pushing young people to gangs”. Click-friendly by all means, but that was not quite what I meant. My text was rather about the lack of things that complement and balance the prevailing discipline focus in debate, politics and classroom practice.

After publication, someone wondered if I was against high demands and discipline. But I’m not at all against it. The process in the figure above requires both high demands on students and self-discipline enough to stick to a challenging goal. I myself certainly know the value of struggling with vocabulary. Because without knowledge of words, I would never have been able to create value for all the exciting Spaniards I met in Madrid. But the reverse is also true. Had there been no exciting Spaniards in Spain, I would never have been able to become fluent in Spanish. It required deep study almost every night, and it was the value of joy and social value that filled Carlos’ reading room in Argüelles with learning oxygen. The school debate should therefore not be about duty versus joy. What we need in school is duty and joy. Two thoughts in the head at the same time.

An emotional lesson this time was that a balanced school is not a particularly click-friendly point to make. Investigative journalists that dig up new scoops are good, but I do not like when they dig trenches in the school debate.

References

Berglind, L. (2016). Ludwig’s answer to the critics: Maybe you are the ones who think that children are stupid in their heads?

Blomé, A., & Simson, W. (2021). Entrepreneurial Failure and Learning – The role of affect in learning from failure and its impact on nascent entrepreneurs Master thesis, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg.

Callahan, G. (2005). Oakeshott and Mises on Understanding Human Action. The Independent Review, 10(2), 231-248.

Carlin, M., & Clendenin, N. (2019). Celestin Freinet’s printing press: Lessons of a ‘bourgeois’ educator. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 51(6), 628-639.

Cooperrider, DL, Whitney, D., & Stavros, JM (2008). Appreciative inquiry handbook: For leaders of change. San Francisco, CA: Crown Custom Publishing Inc.

Ekholm, D. (2018). Youth exclusion in vulnerable neighborhoods: An overview of knowledge about social exclusion in relation to economic conditions, education, political participation and spatial segregation. In: R&D Center for care, nursing and social work.

Hugo, M. (2012). When school learning is meaningless. In L. Mathiasson (Ed.), Assignment Teacher: An anthology on status, professionalism and future dreams Stockholm: Lärarförbundets förlag. pp. 31-38.

Lackéus, M. (2013). Developing Entrepreneurial Competencies – An Action-Based Approach and Classification in Education. Licentiate Thesis, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg. (ISSN: 1654-9732)

Lackéus, M. (2014). An emotion based approach to assessing entrepreneurial education. International Journal of Management Education, 12(3), 374-396.

Lackéus, M. (2016). Value creation as educational practice – towards a new educational philosophy grounded in entrepreneurship? Doctoral thesis, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden. (ISBN 978-91-7597-387-6)

Lackéus, M. (2019). Requirements and discipline in school risk driving young people to gangs. Dagens Nyheter Debate 28/9. Downloaded 2020-10-23 from: https://www.dn.se/debatt/krav-och-disciplin-i-skolan-riskerar-driva-unga-till-gang/.

Lackéus, M. (2020). Comparing the impact of three different experiential approaches to entrepreneurship in education. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(5), 937-971.

Lackéus, M., Lundqvist, M., & Williams Middleton, K. (2016). Bridging the traditional – progressive education rift through entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 22(6), 777-803.

Lackéus, M., & Sävetun, C. (2016). Entrepreneurial education as value creation pedagogy – a third way? An effect study of value creation pedagogy on behalf of the National Agency for Education. Gothenburg: Chalmers University of Technology

Nowacki, MR, & Eecke, W. (2003). The Superiority of ‘Chemical Thinking’for Understanding Free Human Society According to Hegel. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 988(1), 313-321.

Oakeshott, M. (1991). On human conduct. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sandén, I., & Jonsson, I. (2016). I now know how to make a difference!

von Mises, L. (1949). Human action: A treatise on economics. Auburn, Alabama: The Ludwig von Mises Institute.

Wiman, M. (2019). Value creation pedagogy. Stockholm: Lärarförlaget.

Åhslund, I. (2019). Perceptions, expectations and didactic choices – a study of the importance of teaching for boys’ school performance. Licentiate thesis, Mid Sweden University,

[1] Appreciative research is called appreciative inquiry in English and is a leadership theory based on the thesis of studying and expanding what works well, instead of studying what is problematic, see Cooperrider, Whitney and Stavros (2008).

[2] See Lackéus (2014, p.391). See also Lackéus, Lundqvist and Williams Middleton (2016).

[3] See Lacquer (2020).

[4] See Lacquer (2020).

[5] Read about such bridging in Lackéus, Lundqvist andWilliams Middleton (2016).

[6] See Berglind (2016).

[7] See Blomé och Simson (2021).

[8] See Lackéus och Sävetun (2021).

[9] See www.mobilestories.se. Read about Freinet in Carlin och Clendenin (2019).

[10] I have in both my dissertations described value creation pedagogy as an altruistic paradox, se Lackéus (2013, 2016).

[11] See von Mises (1949, s.26) and Oakeshott (1991, s.37). See also Callahan (2005, s.233).

[12] I’ve written about this in Lackéus (2020, s.958).

[13] See Nowacki och Eecke (2003).

[14] See Lackéus (2019).

[15] See for example Hugo (2012), Åhslund (2019) and Ekholm (2018).